The NHS and Migrant Labour

10 March, 2012

Summary

1 The health and social work sector employs one in seven of all immigrants in the UK, and was the biggest employer of migrants between 2002 and 2008; many originated in less developed countries with much poorer and under resourced health care systems.

2 A principal ethical concern is that, while migratory flows of health care staff may benefit some rich countries, they may damage the well-being of those countries they come from. These countries cannot afford the loss of highly qualified professionals who have been expensively trained, especially as their populations often suffer from disproportionate incidence of disease. Concern about migration of health care personnel from poor to rich countries was expressed in the Kampala Declaration (2008), sponsored by the WHO. This is a critical issue for the well-being of many of the poorest countries in the world.

3 The rapid expansion of the NHS as a result of the Wanless Report caused a peak in overseas recruitment of doctors and nurses in 2002 -3. Numbers are now falling but the UK still has a much higher proportion of foreign trained doctors than other comparable European countries, except for Ireland.

Introduction

4 The NHS has been heavily dependent on migrant labour for a number of reasons, some long-standing, others of more recent origin:

- Medical training is expensive, lengthy and represents a substantial investment by governments when financial resources are limited; for this reason, governments have frequently preferred to hire medical professionals from abroad, especially doctors, whose training they have not had to fund, to fill staff shortages

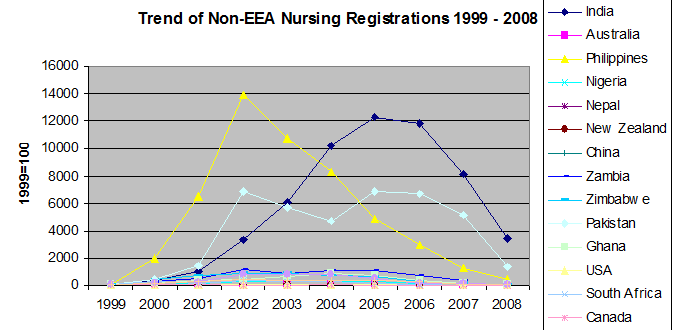

- The Wanless Report into NHS funding[1], published in 2002, identified staff shortages of doctors and nurses as a critical constraint on the achievement of the improved service standards that were deemed necessary. This led to a significant increase in NHS staffing, much of which was sourced internationally

5 In some cases, expertise to the required standard in some clinical fields can only be sourced from abroad. It is undeniable that the NHS in recent years has benefited from clinicians, like the distinguished cardiac surgeon Sir Magdi Yacoub, who were born and trained abroad - in the case of Sir Magdi in Egypt. This is not, however, an argument which can justify the large scale employment of foreign doctors in the NHS, let alone immigration on the scale experienced over the past decade. In 2007 there were 5,005 new registrations with the GMC from doctors trained overseas, less than 1 per cent of the gross total of immigrants to the UK in that year. Furthermore, there are some hazards to the employment of doctors from non-English speaking countries which are at last being acknowledged by the Government.

Countries of Origin of Medical and Nursing Staff in the UK

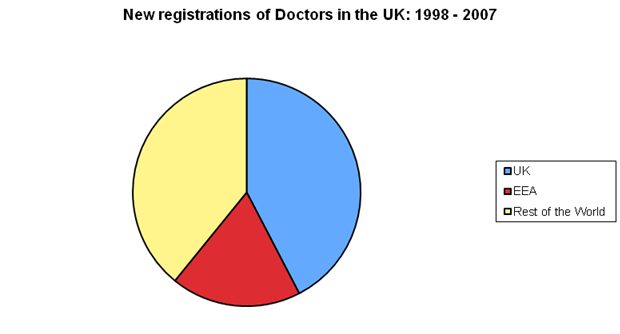

6 The NHS is very heavily dependent on medical and other healthcare professionals who qualified outside Europe. Analysis of data from the Labour Force Survey indicates that in the UK almost a third of medical practitioners and approximately a fifth of dentists, pharmacists and nurses were born outside the European Economic Area (EEA). Based on registration data for the UK’s medical regulator – the General Medical Council (GMC) – 11 per cent of all medical practitioners working in the UK received their qualifications in India. Others qualified in South Africa (3 per cent), in Nigeria (1.4 per cent) and Pakistan and Egypt. Figure 1 below shows that over the decade to 2008, 57 per cent of doctors

registering to practice with the GMC had qualified outside the UK – of these, 18 per cent came from the Europe (the EEA) and almost 40 per cent had been trained outside Europe.

Table 1: New Registrations of Doctors in the UK (based on location of medical qualification), 1998 - 2007

| Year | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

| UK | 4010 | 4242 | 4214 | 4462 | 4288 | 4443 | 4658 | 5164 | 5620 | 6133 |

| EEA | 1590 | 1392 | 1192 | 1237 | 1448 | 1770 | 2419 | 4103 | 2994 | 2446 |

| RoW | 3580 | 2889 | 2993 | 3088 | 4456 | 9336 | 5683 | 5825 | 3163 | 2609 |

| Total | 9180 | 8523 | 8399 | 8787 | 10192 | 15549 | 12760 | 15092 | 11777 | 11188 |

Source: Stephen Bach in Anderson, Ruhs – Who Needs Migrant Workers? ; RoW = Rest of the World

Figure 1: Area of Origin of New Doctor Registrations in the UK: 1998 - 2007

Source: Bach in Anderson, Ruhs

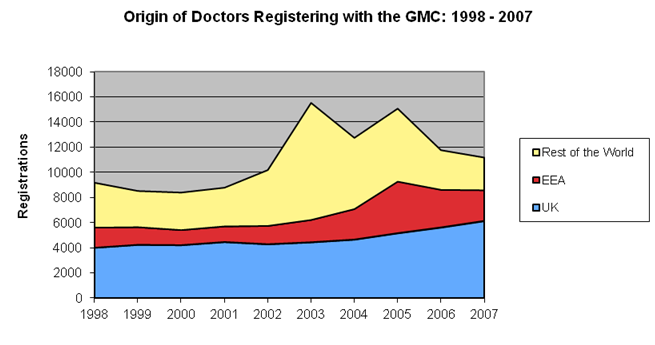

7 Figure 2 shows the trend of doctor registrations with the GMC. What is striking is the surge in doctors from outside Europe in 2003 – the number of such doctors more than doubled in one year – when such registrations accounted for 60 per cent of all doctors registering. By 2007, however, there had been a sharp contraction in recruitment of doctors from outside the EEA, and a corresponding increase in doctors trained either in the UK or EEA countries.

Figure 2: Trend of Doctor Registrations with the GMC

Source: Bach op.cit

8 The extent of NHS reliance on foreign-trained doctors is much higher than for most other countries in Europe, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Foreign Trained Doctors as Share of all Doctors – Various European Countries – 2004 - 2007

| Country | Percentage |

| Austria | 3.3 |

| Denmark | 10.9 |

| Finland | 7.2 |

| France | 5.8 |

| Germany | 4.9 * |

| Ireland | 30.1 |

| Italy | 3.5 * |

| Netherlands | 6.2 |

| Poland | 0.7 |

| Switzerland | 18.8 |

| UK | 37.5 |

Source: WHO Europe

* Foreign doctors (no data on where they were trained)

Table 3 below shows the breakdown by specialisation of EEA and non EEA health professionals in the UK

Table 3: EEA and Non-EEA Origins of Selected Health Professionals

| Employees Born Non-EEA (%) | Employees Born EEA (excluding UK - %) | Estimated Numbers of Working-Age UK Population in this Occupation | |

| Medical Practitioners | 32 | 5 | 184,000 |

| Psychologists | 19 | 4 | 23,000 |

| Pharmacists | 21 | 5 | 40,000 |

| Opthalmic Opticians | 4 | 1 | 13,000 |

| Dental Practitioners | 20 | 5 | 27,000 |

| Nurses | 19 | 3 | 500,000 |

| Midwives | 12 | 9 | 37,000 |

| Paramedics | 8 | 2 | 17,000 |

| Medical Radiographers | 8 | 4 | 25,000 |

| Chiropodists | 9 | 0 | 10,000 |

| Dispensing Opticians | 5 | 8 | 5,000 |

| Physiotherapists | 9 | 4 | 32,000 |

| Occupational Therapists | 5 | 6 | 31,000 |

| Speech and Language Therapists | 4 | 0 | 14,000 |

Source: Bach.

9 Figure 3 below shows index numbers, based in 1999, charting trends in numbers of nurses born outside the EEA registering to work in the UK. Noteworthy, is the sharp increase in nurse numbers from outside the EEA coming to work in the UK. In the peak year 2001/02, only 47 per cent of new entrants had qualified in the UK compared to almost 90 per cent in the early 1990s. The major countries of origin have been Australia, India and the Philippines. For the Philippines, nurse registrations increased from 52 in 1999 to over 7,200 in 2002. The chart shows the subsequent contraction in numbers a few years later as the NHS curtailed active overseas recruitment after 2005. In 2002, the number of these nurse registrations peaked at just over 15,000, less than 3 per cent of the gross inflow of immigrants into the UK in that year.

10 The number of nurses from EEA countries working in the UK has always been significantly lower than those from outside Europe due to language and other barriers.

Figure 3: Trend in Nurse Registrations in the UK: 1999 – 2008

Source: Bach op.cit

Challenges in the Employment of Health Care Professionals from non-English Speaking Countries

11 Following concerns about the English language competence of medical staff from Europe working in the UK, the Health Secretary, Andrew Lansley, announced in October 2011 that doctors from Europe who wished to work for the NHS in England would be tested to ensure that their language skills are adequate. Doctors from non-European countries, like India and the Philippines, are already tested for language competencies.

12 Other staff, such as nurses, health care assistants, and auxiliary workers from non-English speaking countries will not be subject to such formal testing despite having contact with patients but the need – in terms of patient safety – is arguably less critical.

Evidence to the Migration Advisory Committee

13 In its report on limiting migration, the Government’s Migration Advisory Committee noted (para. 8.12, p.170):

“Evidence provided by the Department of Health (DH) indicated that, as of September 2009, 24 per cent of medical professionals working full-time at consultant level and 33 percent of medical professionals working full-time in the registrar group (doctors that are below consultant grade) graduated from medical schools outside the EEA. Although some of these graduates may be UK and EEA citizens who studied abroad, it is likely that a large proportion of these medical professionals are non-EEA migrants.”

14 Employment of health workers from outside the EEA is more intense in some clinical sectors than others. Paediatric neurology (25 per cent), paediatric cardiology (18 per cent) and chemical pathology (13 per cent) are areas with greater than average dependence. In contrast, in some other occupations the proportion is much smaller – in diagnostic radiography it is 3 per cent and in orthoptic therapy only 1 per cent.

The Migration Advisory Committee noted in its report (para. 8.15, p.171) that:

“According to DH (Department for Health), the NHS has historically relied on the recruitment of migrant workers to fill vacancies in specific regions and specialisms, and also to rapidly expand the workforce in areas that would normally depend on long lead times to train sufficient numbers of the existing UK workforce. DH told us that the UK is moving towards greater self-sufficiency in terms of NHS workforce supply, although this will not be achievable in the short term or in all occupations and regions.”

Global Shortage of Health Care Professionals

15 The WHO estimated in 2006 that there was a worldwide shortage of 4.3 million health workers, highlighting 57 countries where there were particularly severe shortfalls; 36 of these countries are in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa, has 11% of the world's population and 24% of the global burden of disease but only 3% of the world's health workers. Annex A shows indicators of health and health care provision in the UK and in those countries from where many immigrants to the UK have been recruited to work in the NHS. South Africa and the countries of the Indian Sub-Continent are conspicuous as having major health care needs and deficient health care provision. In India for example, where NHS recruitment has not been subject to the same curbs that have been applied to the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, and where over a tenth of physicians working in the UK originated, life expectancy at birth is 15 years less than in the UK and infant mortality is nine times higher, whilst TB incidence is fifteen times higher.

16 In response to this situation, British Government issued guidance in 1999 for NHS employers which listed those countries – mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa – from which it considered it would be unethical to source health workers. It is not clear that the private sector followed a similar policy.

Kampala Declaration

17 In March 2008, the WHO convened a conference in Kampala, Uganda, to discuss the shortage of health care staff and agree a programme of action. A statement of intent – the ‘Kampala Declaration’ – was issued at the end of the conference which, inter alia, stated that:

“ While acknowledging that migration of health workers is a reality and has both positive and negative impact, countries [are asked] to put appropriate mechanisms in place to shape the health workforce market in favour of retention. The World Health Organization will accelerate negotiations for a code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel.

“All countries will work collectively to address current and anticipated global health workforce shortages. Richer countries will give high priority and adequate funding to train and recruit sufficient health personnel from within their own country”

Sources of Data

Global Shortage of Health Workers

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2006/pr19/en/index.html

Kampala Declaration

http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/forum/2_declaration_final.pdf

Language Testing of Non-English Speaking Doctors:

http://mediacentre.dh.gov.uk/2011/10/04/foreign-doctors-must-prove-they-can-speak-good-english/

Migration Advisory Committee: Limits on Migration (November 2010)

http://www.ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk/sitecontent/.../mac-limits-t1-t2/report.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO): Health for All

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_for_all

WHO: Migration of Health Personnel in European Region

http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/95689/E93039.pdf

The key source for much of the material in this paper is:

Ruhs, M and Anderson, B (Eds) (2010) Who Needs Migrant Workers? Labour Shortages, Immigration, and Public Policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Annex A : Data on Healthcare Provision and Health for Countries of Migration of Health Care Professionals to the UK

| Country | Population | Density of Physicians | Density of Nurses | Number of Physicians | Number of Nurses | ‘Shortage’ of Physicians | ‘Shortage’ of Nurses | Life Expectancy @ Birth | Infant Mortality Rate (per 1000) | HIV | TB |

| India | 1198003 | 0.599 | 1.297 | 660801 | 908962 | -2620529 | -1+1E+0.7 | 65 | 48 | 0.3 | 185 |

| Pakistan | 180808 | 0.813 | 0.557 | 139555 | 69313 | -355678 | -1793371 | 63 | 70 | 0.1 | 231 |

| Philippines | 91983 | 1.153 | 6 | 93862 | 352398 | -158079 | 2575789 | 70 | 23 | 0.1 | 275 |

| Poland | 38074 | 2.144 | 5.729 | 82397 | 197929 | -21888 | -194309 | 76 | 5 | 0.1 | 23 |

| S Africa | 50110 | 0.77 | 4.08 | 34829 | 184459 | -102395 | -331744 | 54 | 41 | 17.8 | 971 |

| Zimbabwe | 15523 | 0.16 | 1.485 | 2086 | 9357 | -32215 | -119655 | 49 | 51 | 14.3 | 633 |

| UK | 61565 | 2.739 | 10.302 | 165317 | 589025 | 80 | 5 | 0.2 | 13 |

Source: WHO; MWUK calculations

Notes:

- Most data is for 2008 or 2009

- Density of Physicians/ Nurses – number of physicians and nurses per 1,000 population

- ‘Shortage’ of Physicians or Nurses – a benchmark of numbers of doctors and nurses against those in the UK, calculated as the difference between actual numbers of physicians and nurses, and the additional number that would be needed to bring their staff numbers up to the level in the UK

- HIV – prevalence (%) of HIV amongst adults aged 15 to 49

- TB – incidence per 100,000 population.

ANNEX B: Overseas (non-EEA) Trained Nurses Registered Per Annum in the UK, 1999 – 2008

| Country | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

| India | 30 | 96 | 289 | 994 | 1830 | 3073 | 3690 | 3551 | 2436 | 1020 |

| Australia | 1335 | 1209 | 1046 | 1342 | 920 | 1326 | 981 | 751 | 299 | 262 |

| Philippines | 52 | 1052 | 3396 | 7235 | 5593 | 4338 | 2521 | 1541 | 673 | 249 |

| Nigeria | 179 | 208 | 347 | 432 | 509 | 511 | 466 | 381 | 258 | 154 |

| Nepal | - | - | - | - | 71 | 43 | 73 | 75 | 148 | 117 |

| N Zealand | 527 | 461 | 393 | 443 | 282 | 348 | 289 | 215 | 74 | 62 |

| China | - | - | - | - | - | - | 60 | 66 | 80 | 52 |

| Zambia | 15 | 40 | 88 | 183 | 133 | 169 | 162 | 110 | 53 | |

| Zimbabwe | 52 | 221 | 382 | 473 | 485 | 391 | 311 | 161 | 90 | 49 |

| Pakistan | 3 | 13 | 44 | 207 | 172 | 140 | 205 | 200 | 154 | 42 |

| Ghana | 40 | 74 | 140 | 195 | 251 | 354 | 272 | 154 | 66 | 38 |

| USA | 139 | 168 | 147 | 122 | 88 | 141 | 105 | 98 | 21 | 35 |

| S Africa | 599 | 1460 | 1086 | 2114 | 1368 | 1689 | 933 | 378 | 39 | 32 |

| Canada | 196 | 130 | 89 | 79 | 52 | 89 | 88 | 75 | 31 | 24 |

| Kenya | 19 | 29 | 50 | 155 | 152 | 146 | 99 | 41 | 37 | 19 |

| TOTAL | 3621 | 5945 | 8403 | 15064 | 12730 | 14122 | 11477 | 8709 | 4830 | 2309 |

Source: Bach, op.cit

Footnotes

- Securing our Future Health: Taking a Long-Term View. April 2002

- Securing our Future Health: Taking a Long-Term View. April 2002