International Students: The Case for Refining their Visa Regime

18 February, 2014

Summary

1. The Tier 4 student visa should be divided into three visas, one for each type of study: University, Further Education, and English Language. This would allow for a better understanding of the international student sector and for greater flexibility in entry requirements that properly reflects the different risks that exist in each part of the sector.

Introduction

2. During the Labour years net migration increased dramatically to levels never before experienced; workers, students and family migrants migrated to the UK in the hundreds of thousands. The system was also increasingly chaotic. The public saw large inflows of migrants, backlogs of asylum claims and Home Secretary after Home Secretary sacked following the latest immigration crisis. The public opposed the level of immigration that was being experienced, understanding the consequences of an inflow of nearly four million foreign migrants on public service provision and community cohesion. There was virtually no confidence in the system.

3. It was against this backdrop that the Conservative party pledged to reduce net migration from the hundreds of thousands to the tens of thousands. The Home Secretary in her first major speech on immigration committed herself to restoring faith in the immigration system.[1]

4. The target of net migration in the tens of thousands remains elusive. A significant amount of abuse has been eliminated and the system has been tightened. The consequence of this is that non-EU net migration is at its lowest level since 1998.

5. Yet overall net migration remains unacceptably high – 182,000 in the year ending June 2013. There are three main reasons for this: levels of British emigration are historically low[2], EU migration is increasing[3] and finally because non-EU migrants depart at less than half the rate that they arrive. Non-EU migrants are either staying on legally by extending their visas and gaining indefinite leave to remain or they are staying on illegally once their visa expires. Overseas students comprise about 60% of the inflow from outside the EU.

6. Reducing net migration remains a central aim however it must also be achieved intelligently. The reforms must also be good for the country overall. Businesses need to recruit overseas workers where there are skills gaps in the labour market and Universities need the finance and dynamism that comes from overseas students. This means that a balance must be struck between immigration control and the needs of the business and education sector.

7. It is clear that businesses are not being harmed by the regime that governs work migration. There is a cap of 20,700 Tier 2 visas per year and only half of these have been taken up. Moreover, Tier 2 inter-company transfers (ICTs) are exempt from this limit and various new visa routes have been opened with the express intent of attracting the world’s brightest and best to these shores to start and build their businesses.

8. In terms of the student route, there is more than can be done to ensure that the system works better for overseas students, the education establishments and local communities. Fee paying international students should be welcomed to our finest Universities, colleges and language schools and graduates who stay on to develop their ideas and build successful businesses are positive for us all. At the same time, we should recognise that students staying to work after their studies will compete with British graduates among whom recent graduate unemployment is at 10%[4]. Worse still, some students stay on illegally to work in the black market and undercut local wages.

9. This paper puts forward the case for splitting visas for non EU students into three constituent parts: a university visa, a further education visa, and a language visa. (EU students do not, of course, need a visa). Such a system would provide better information about student behaviour, more flexible entry requirements and a better assessment of immigration risk.

Principles that should underpin the system

10. It is in everyone’s interests to establish a system that benefits the entire country, and not just the vested interests of the education establishments themselves. Just as unlimited cheap labour might be good for companies wishing to pay low wages but disastrous for the existing low paid in society, there are competing interests to consider in an ideal student visa system.

11. The reality is that the scale of overseas students and effective immigration control are in tension so there is a balance to be struck.

12. It is therefore helpful to outline some guiding principles:

- Immigration control is a legitimate aim and controlling the entry of students is a part of this.

- Immigration control and student immigration are in tension and the needs of the education sector must be balanced against other considerations, including the needs of the labour market, the existing labour force, the views of the electorate etc.

- The provision of education to overseas students is a major export industry and is worth a significant sum in both financial terms and ‘soft power’.

- The British education system has an excellent reputation. Abuse of the system undermines this position and should not be tolerated.

The Points Based System Tier 4 Visa 2008-2010

13. In 2008 the Labour government introduced the Points Based System, a new immigration system that was designed to select migrants based on objective criteria rather than subjective judgements by Entry Clearance Officers (ECOs). Criteria included previous qualifications, language ability and available funds. The Points Based System, it was argued, would restore trust in the immigration system. It was also a misguided effort to save money, although even today, and despite their importance, less than a quarter of a percent of total government expenditure is spent on immigration controls.

14. The system however, was fatally flawed from the start. To begin with there was no upper limit on the number of people who could come to the country in any given year. Nor were there any means of weeding out bogus applicants since interviews had been abolished.

15. Following the introduction of the PBS the student route was abused on a huge scale. Anyone wishing to move to the UK could get a student visa simply by having a sufficient amount of money in their bank and by having a place at a UK education establishment. Bogus colleges appeared above takeaways and restaurants on high streets across the country. These ‘colleges’ issued the bogus applicant with a place on a course in return for a fee. Once the visa was granted, neither the student nor the college had any interest in the other being genuine: the bogus student had gained entry into Britain and the bogus college had their money. Some unfortunate students unwittingly paid fees to bogus colleges and were left out of pocket and in limbo.

16. Towards the end of 2009 the government was forced to suspend student visa applications in China, North India, Bangladesh and Nepal due to concerns that the significant rise in applications was fuelled by bogus students and organised scams.[5] These suspensions were not fully lifted until August 2010.[6] A Parliamentary question shows that in the third quarter of 2008 there were 22,944 Tier 4 Student applications in India. In the third quarter of 2009 this number had risen to 54,749.[7] A similar pattern existed in those countries where Tier 4 activity was suspended.

17. In 2012 the National Audit Office investigated the administration of the student route of the PBS in its first years of operation and found that in the first year alone as many as 50,000 bogus students may have come to work rather than study. The report notes that a third more student visas were granted in the first year of the PBS, ‘an increase not explained fully by external economic changes, such as increased prosperity in some countries and movements in exchange rates.’[8] These surges took place in particular countries including India, Bangladesh and China and were generally in relation to applications for English language courses and lower level courses at private institutions.[9]

The Points Based System Tier 4 Visa - 2010 to the present day

18. Following the election in 2010, the Home Secretary began reforming each element if the immigration system. The student route underwent significant reform in terms of both the requirements of the education institutions and of students.

19. From 2011 the government required that all education institutions acquire Highly Trusted Sponsor status and thus be subject to a stricter set of requirements with regard to their levels of compliance. Furthermore all institutions had to be accredited by an appropriate education body. Since then around 600 bogus colleges have been closed down.[10]

20. The employment rights of certain students were restricted. Only students that were studying at a university or a publicly funded further education college could seek employment and the number of hours that a student could work was made dependent upon the level of their course. Those studying at a privately funded education provider were restricted from working under the reforms.

21. The right to sponsor dependants was also restricted; only students studying at postgraduate level for longer than 12 months were permitted to be accompanied by their dependants.

22. The government also increased the English language competence required of students in response to anecdotal evidence that students were entering the country to study despite not speaking a word of English. Applicants wishing to study at Universities were exempt and universities were given the discretion to assess language competence.

23. Finally, the Tier 1 Post Study Work visa, a two year visa that allowed all graduates of any subject and any grade to remain in the UK for two years to work was also abolished. The evidence suggested that around 60% of post study work visa holders were working in low skilled jobs such as security guards or shop assistants.[11]

24. Instead, students would be granted an additional four months following the completion of their studies during which they could look for work. If the student could secure a graduate level job that paid a minimum of £20,000 with a recognised sponsor then an unlimited number could switch into Tier 2, bypassing the cap and the resident labour market test that applies to those wishing to come to work on a Tier 2 visa from outside of the UK.[12]

25. In addition to these reforms, in December 2011, the Home Office conducted a three month student interview pilot scheme to assess the usefulness of interviews with a view to reintroducing them. The scheme piloted a credibility assessment made up of four elements: a students’ intention to study the proposed course, their ability to study the course, their ability to support themselves and any dependants for the duration of the course, and finally their intention to leave the UK at the end of their course. The pilot scheme found that in India, Nigeria, Bangladesh and Burma around 60% of those interviewed could potentially have been refused a visa on credibility grounds. In the Philippines this number was 53%, in Pakistan 48% and in Sri Lanka this number was 41%.[13] The Home Office announced that from April 2013 around 100,000 student applicants would face interviews in order to further strengthen the system that had proved incapable of rooting out abuse.[14]

26. The student route thus underwent significant reform between 2010 and 2013, during which a robust approach was taken with regards to the quality of education institutions that were granted the right to sponsor students and to the credibility of applicants.

The Implications of Changes to the Student Visa Regime

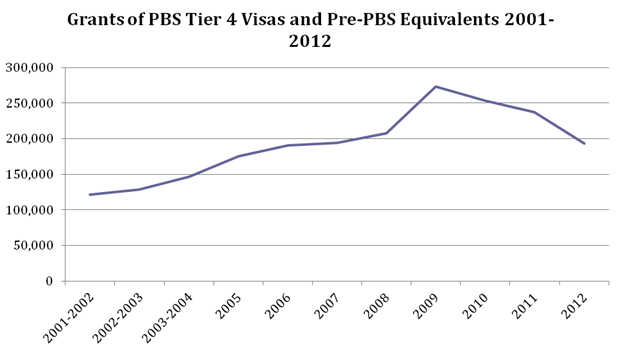

27. Student numbers rose dramatically following the introduction of the PBS and then fell significantly following the student reforms. The graph clearly shows this pattern.

Figure 1. Grants of PBS Tier 4 Visas and Pre-PBS Equivalents, 2001-2012 (Excluding Student Visitors and Dependants)

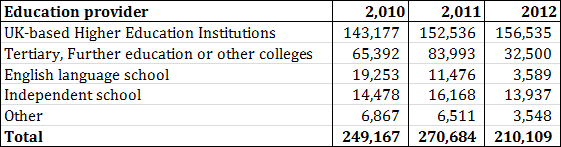

28. Within this however, visa application data shows that applications to study at universities have increased and that the reduction has taken place in the further education sector. The reduction in applications for English language schools is a result of the student visitor visa increasing from 6 to 11 months, meaning that most language students no longer require a Tier 4 visa.

Table 1. Applicants for visas for study using sponsor acceptances, by education sector

Further Student Visa Reform

29. While the main problem with the pre-reformed PBS, the absence of interviews to assess the credibility of candidates, has now been remedied there is a case for one further administrative change that would ensure that there was better information available about student behaviour, would introduce greater flexibility and would allow for a system to develop that implicitly recognised the varying levels of immigration risk that exists in certain sectors.

30. We propose that the Tier 4 (General) visa be broken up into three different visas: Tier 4 university study visa, Tier 4 further education study visa and a Tier 4 English language study visa. There would be no change to the Tier 4 (Child) visa or student visitor visa.

31. In terms of the existing immigration system a subdivided Tier 4 (General) visa would not be unlike the Tier 2 work route which is divided into four sub categories (General, ICT, Minister of Religion and Sportsperson) or Tier 5 Temporary Workers which is also subdivided into six categories. Tier 2 and Tier 5 contain sub categories which accurately reflect the diversity of those migrants that enter the country on that visa.

32. In 2012 almost 200,000 visas were granted to non EU students (excluding student visitors and dependants). It is difficult for a single visa to capture the complexities of such a large cohort of people attending very different types of education institutions: universities, business schools, private colleges, publicly-funded or privately funded further education colleges and language schools.

33. We in fact know very little about students and their patterns of behaviour. Table 1 above shows us the number of applicants to each type of institution and we know the number of students granted visas overall but other than this we know very little. There is no data on visa grants by institution type, admission into the country by institution type, switching into work categories by institution type or departure by institution type. A sub-categorised student visa would thus provide the Home Office and the education sector with a wealth of data that would allow for a better understanding of overseas student behaviour.

34. Crucially, in terms of overall immigration policy, the proposed change would help develop a better understanding of the patterns of departure of students based on their visa type. In recent years there has been an absence of data on student departures. The Migrant Journey report, published in 2010, suggested that after five years 80% of students visas had expired and therefore students had no valid leave to remain.[15] For a long period of time this was all the data available and there was no data on the number of students who had actually left the country. This was because exit checks had been abolished in the late 1990s and the International Passenger Survey (IPS) was incapable of distinguishing between workers and students leaving the country as they both appeared in the statistics as emigrating for the purposes of work. The IPS has now been amended and data for the first year or so suggests that students are departing at a third of the rate that they are arriving.[16] Unfortunately we do not know anything about the 49,000 non-EU students who departed in 2012 and whether they came to study at university or a further education college. Such information would be helpful in monitoring flows and risk. Using the e-Borders system it would be possible to identify outflows by institution type under this proposal. The system would also be able to identify which types of student switch into Tier 1 and Tier 2 at the end of their studies as well as those who go on to settle.

35. A disaggregated visa system would also allow for additional requirements and conditions to be attached to a specific visa where appropriate and would remove unnecessary requirements for others. For example the government requires that all non-university Tier 4 applicants demonstrate an acceptable level of spoken English currently set at Level B1 on a common European framework. This requirement rather perversely also applies to those wishing to study at an English language school, meaning that people who have no proficiency in English cannot learn English here on a Tier 4 visa. This is no doubt a concern for the English language school sector although most language students will enter the country on the extended 11 month student visitor visa which has no language requirement. This does not cover all English language courses and pre-access courses which often include a language element. Under this proposal the English language visa could have more appropriate language conditions attached. Similarly, if the government wished to restrict or expand rights for certain types of student, this could be done without concern that particular students were being unfairly treated.

36. The abuse that has taken place has largely been confined to certain sections of the education sector as discussed in paragraphs 14 to 17 above. Since the evidence shows that there is a greater risk associated with certain types of institutions it would be sensible for students wishing to study at higher risk institutions to be subject to greater scrutiny in terms of their application. The proposed system would allow for University applicants – who are lower risk in terms of their overall compliance – to be subject to fewer or less rigorous requirements than higher risk applicants who wish to study at privately funded further education establishments where most abuse has taken place.

37. The recent BBC Panorama programme has exposed fraud in the student visa system in the non-University sector. The programme uncovered agents assisting in making fraudulent applications for visa extensions and invigilators from an approved English language testing company reading out the answers to candidates as well as candidates having their tests sat for them by competent English speakers.[17] That this kind of fraud exists in the lower end of the education sector suggests that there should be a more rigorous regime in place for those studying in that sector; this could be better implemented under the visa system we propose. The evidence from this programme also suggests that interviews should not simply be confined to those applying to study in the UK for the first time but should also be extended to those making applications to extend their stay.

38. From an international perspective there is precedent. The Australian system – one of the UK’s biggest competitors and a country held up by the education sector as an example to the UK – offers seven different types of visas depending on the type of institution and level of study including an English Language Visa, a Vocational Education and Training Visa, a Higher Education visa, and a Postgraduate Research Visa.[18] Applicants are also given a risk level based on their nationality and the type of visa that they require. In the higher risk cases there is a more rigorous assessment of the applicant before the visa can be granted. Only by subcategorising students as suggested can the UK implement a system whereby students are assessed according to the immigration risk that they pose. This should act as a major incentive to adopt the proposal.

Conclusions

39. Given the importance of overseas students to our Universities and their value to our economy it is essential that the Home Office create a student visa system that maximises the benefits for both the education sector and wider society. Other considerations must also include the needs of the wider labour market, the existing labour force, public opinion and society generally. The current single study visa is too inflexible to allow the education sector to grow and flourish while also ensuring that abuse is tackled and that public confidence in the system is maintained. The system should be replaced with one similar to the Australian visa system with distinct visas granted for different types of study. This would allow the government to work with the education sector to address their specific concerns and to ensure that students themselves can move smoothly through the system, maximising the UK’s attractiveness. Such a subcategorised visa system would allow for greater flexibility in terms of entry requirements which would take account of immigration risk which is considerably greater in some sectors than in others.

Footnotes

- Home Secretary, Speech 5th November 2010, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/theresa-may-vows-to-restore-public-confidence-in-immigration-system

- British emigration is historically low likely as a result of the legacy of the global recession. The net outflow of British citizens peaked in 2006 when 124,000 more British citizens departed than arrived (IPS). The latest statistics show a net outflow of just 64,000.

- EU migration reached its peak in 2007 when there was a net inflow of 127,000 (according to the IPS). This fell to 58,000 in 2009 however has since risen to 106,000. This is largely as a result of an inflow from the EU15 countries due to economic difficulties.

- ONS, Graduates in the UK Labour Market 2013, November 2013, URL: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_337841.pdf

- House of Commons Standard Note, Immigration: International Students and Tier 4 of the Points Based System, SN/HA/05349, 23 July 2010, URL: http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN05349.pdf

- National Audit Office, Immigration: The Points Based System – Student Route, March 2012, URL: http://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/10121827.pdf p. 14.

- Show -6 more...

- Home Secretary, Speech 5th November 2010, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/theresa-may-vows-to-restore-public-confidence-in-immigration-system

- British emigration is historically low likely as a result of the legacy of the global recession. The net outflow of British citizens peaked in 2006 when 124,000 more British citizens departed than arrived (IPS). The latest statistics show a net outflow of just 64,000.

- EU migration reached its peak in 2007 when there was a net inflow of 127,000 (according to the IPS). This fell to 58,000 in 2009 however has since risen to 106,000. This is largely as a result of an inflow from the EU15 countries due to economic difficulties.

- ONS, Graduates in the UK Labour Market 2013, November 2013, URL: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_337841.pdf

- House of Commons Standard Note, Immigration: International Students and Tier 4 of the Points Based System, SN/HA/05349, 23 July 2010, URL: http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN05349.pdf

- National Audit Office, Immigration: The Points Based System – Student Route, March 2012, URL: http://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/10121827.pdf p. 14.

- Parliamentary Question from Mr Frank Field, Hansard Reference 1264W, 6thApril 2010, URL: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmhansrd/cm100406/text/100406w0028.htm

- National Audit Office, Immigration: The Points Based System – Student Route, March 2012, URL: http://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/10121827.pdf p. 15

- National Audit Office, Immigration: The Points Based System – Student Route, March 2012, URL: http://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/10121827.pdf p. 14

- Parliamentary Under Secretary of State, Home Office, Lord Taylor of Holbeach, House of Lords Debate on Student Visa Policy, 31st January 2013, Column 1726. URL: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201213/ldhansrd/text/130131-0002.htm

- UK Border Agency, Points Based System Tier 1: An Operational Assessment, October 2010, URL: http://www.ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk/sitecontent/documents/aboutus/statistics/pbs-tier-1/pbs-tier-1.pdf

- Employers wishing to recruit overseas workers first have to complete a resident labour market test to ensure that they are not able to recruit from within the European Union.

- Home Office, Tier 4 student credibility pilot analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, July 2012, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/115920/occ104.pdf

- Theresa May, Speech to Policy Exchange, 12th December 2012, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/home-secretary-speech-on-an-immigration-system-that-works-in-the-national-interest

- Home Office, Migrant Journey Research Report 43, September 2010, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/116042/horr43-summary.pdf

- Migration Watch UK, Foreign Students – How many have left?, October 2013, URL: http://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/2.25

- Richard Watson, BBC, ‘Student visa system fraud exposed in BBC investigation’, 10 February 2014, URL: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-26024375

- Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Student Visa Programme Quarterly Report, September 2013, URL: http://www.immi.gov.au/media/statistics/study/_pdf/student-visa-program-report-2013-09-30.pdf