An Assessment of the Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK

13 March, 2014

Summary

1. The fiscal effect of immigration on the UK exchequer has gained considerable prominence in recent months. The results of all research in this area depend on the method used and on the assumptions underlying them. This paper examines a “discussion paper” issued by the Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM) at University College, London. The authors, Dustmann and Frattini, adopted the “average cost” method for their reported results but also calculated an alternative scenario using the “marginal cost” method preferred by some. This paper focuses on the reported results, but we also examine the alternative scenario in Annex A.

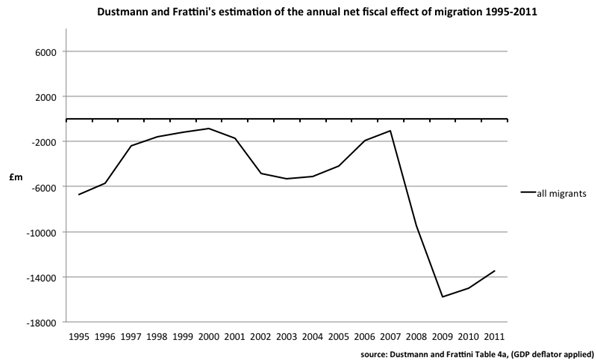

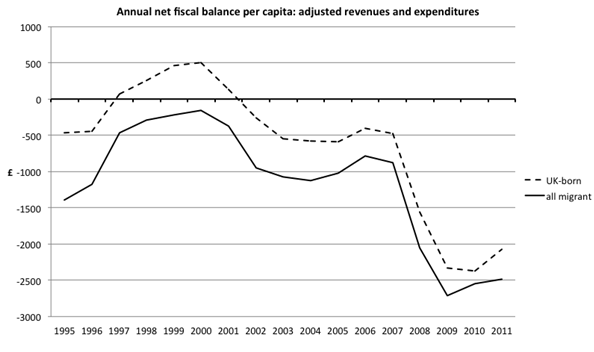

2. The authors themselves found a fiscal cost to the UK from migrants in the UK of £95 billion between 1995 and 2011. This result can be found only in Table 5 at the end of their paper; the figure is not mentioned in their text and the abstract of their paper makes no mention of any fiscal cost at all. Furthermore, their findings show a net cost every year as illustrated below.

Fig 1.

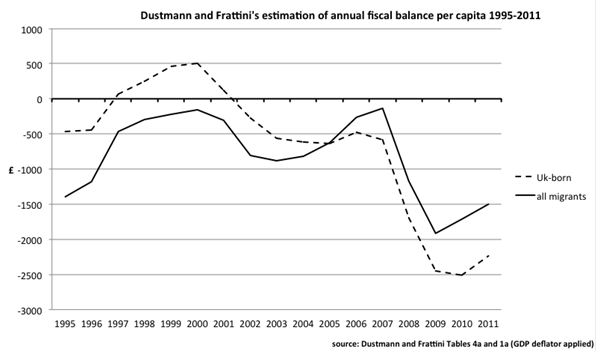

3. They also found consistently negative net per capita contributions by migrants - even when the UK-born were contributing positively.

Fig.2

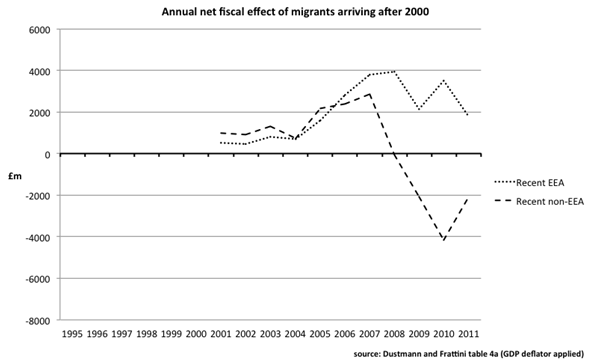

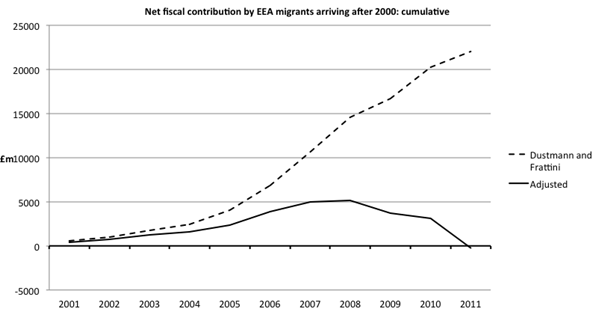

4. The authors claim that this masks a different and much better performance by recent migrants from both within and outside the EEA.

Fig.3

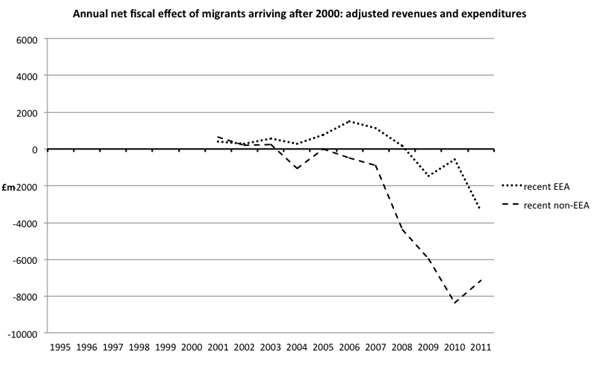

5. This paper from Migration Watch UK makes clear that Dustmann and Frattini have overstated revenues and understated expenditures for these recent migrants, and suggests something quite different when they are adjusted to take account of these, as shown below.

Fig.4

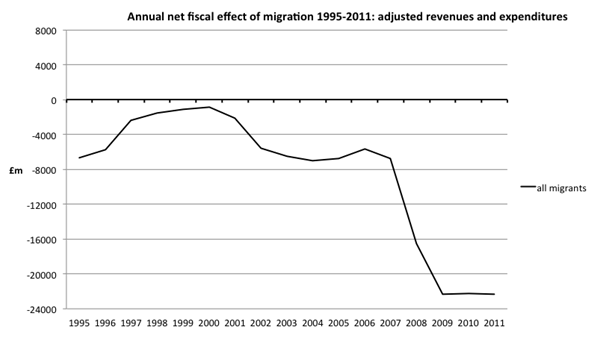

6. Our adjustments make the contributions by migrants consistently negative as Dustmann and Frattini also found, but worse each year than the contributions made by the UK-born.

Fig.5

7. These adjustments suggest that the overall fiscal cost of migration to the UK – assuming that Dustmann and Frattini were otherwise correct - was £148 billion during the period from 1995-2011.

Fig.6

8. Dustmann and Frattini claimed in particular that between 2001 and 2011 recent EEA migrants contributed to the fiscal system 34% more than they took out, with a net fiscal contribution of £22 billion. We suggest that in fact there was no positive contribution.

Fig.7

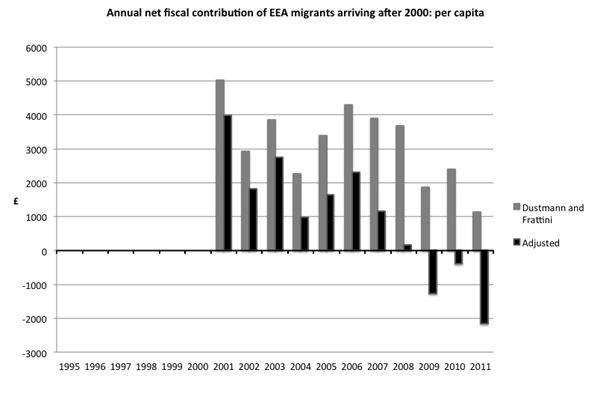

9. Annual per capita contributions show the clear downward trend of Dustmann and Frattini’s findings, and the result of adjustment to take account of their overstatement of revenues and understatement of expenditures.

Fig.8

10. The headline conclusions of their press release have been very widely repeated and publicised, most commonly that for EEA migrants since 2000:

- They contribute 34% more than they receive.

- This amounted to over £20 billion from 2001-2011.

- They are only half as likely to claim state benefits as the general population.

11. We have found, on examination that:

- The claim that recent EEA migrants contributed 34% more in revenues than they received in state expenditures is simply wrong. It relies on assumptions that employees earn the same as the UK-born population when their own figures show they do not, that self-employed migrants contribute far more than those employed when they have no evidence of this whatsoever and – wholly unrealistically - that all of them own the same investments, property and other assets as the UK-born and long-term residents from the day they arrive in the UK.

- In fact, on less unreasonable assumptions, there was no positive fiscal impact at all from the recent EEA migrant group singled out by Dustmann and Frattini for their “very positive contribution”. Indeed, migration to the UK continues to have a significant fiscal cost, and recent migrants made no difference to the upward trend.

- The claim that recent EEA migrants are only half as likely to claim ’benefits or tax credits’ is highly misleading. Indeed it is meaningless in the context of establishing the fiscal cost since what matters is the amount people receive rather than the number of claims made – especially since different benefits pay widely different amounts to different people. Recent EEA migrants are much more likely to receive tax credits than the UK-born population, and more likely to receive housing benefit. Furthermore, these are likely to be paid at higher rates in view of their lower incomes. Typically they will be higher than the out-of-work benefits they are less likely to claim, and the native born more likely, to claim. For example in 2011, typical out-of-work benefits for a couple with two children were around £200 a week , but the same couple in low-paid work with two children could be receiving twice that much as they become entitled to working and child care components of tax credits. Job-seekers Allowance was £67.50 a week but the average housing benefit claim was between £73 and £145 per week.