The Demand for Housing in London

15 October, 2014

Key Findings

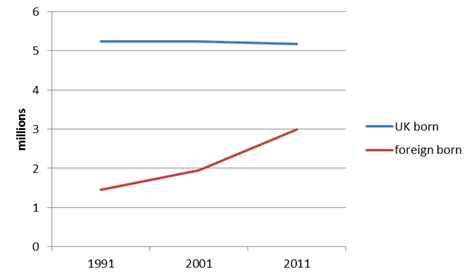

- London’s huge population increase in the last two decades and resulting housing shortage has been driven solely by immigration. The UK born have remained at 5.2 million while the foreign born have doubled to 3 million.

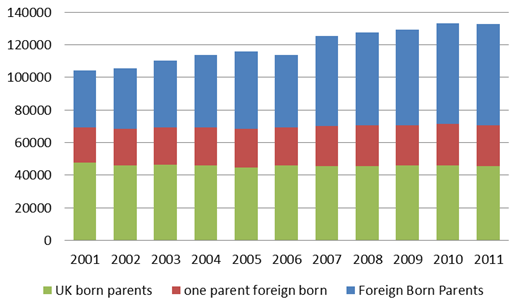

- The majority of children born in the capital are now to foreign born parents. Between 2001 and 2011 540,000 children were born to parents who were both foreign born while 505,000 were to parents who were both UK born. In 2012 only one third of births were to parents who were both UK born.

- Housing supply has not kept pace with population growth and is under huge pressure. The waiting lists for social housing have doubled since 2000, property prices have soared and overcrowding has increased.

- Too many households chasing too few homes has also resulted in existing residents being displaced from the capital to elsewhere in England.

- At local authority level in London there is a clear correlation between the net inflow of international migrants and the net outflow of residents.

- London’s population is projected to continue to grow, to 10 million in the next fifteen years, driven by international immigration and births to the current and future immigrant population.

- The city’s Housing Strategy seriously misrepresents the reason for the projected growth claiming it is down to “primarily the natural growth that results from London’s relatively youthful population”.

- In fact over 1.1 million immigrants are projected to come to London over the next fifteen years. These future migrants, along with those migrants already here will continue to produce the majority of children born in the capital.

- The Mayor has ambitious plans to deal with this future population growth by doubling the level of house building in the capital to 42,000 homes a year.

- However, even this increased level of house building still relies on a continuing exodus of over one million Londoners from the city in the next fifteen years.

- Failure to build the target of 42,000 homes every year in London will result in even greater pressure on the housing stock so that even more people will have leave the city to find somewhere suitable to live. This will have important consequences for the surrounding regions.

London’s Population

1. London’s population has always been constrained and influenced by the availability of housing. During the 19th century London grew rapidly due to a high birth rate[1] and migration to the city from other parts of England[2]. This led to severe pressure on the city’s housing with many of the innermost districts having over half their population living in overcrowded conditions (then defined as over 2 people per room) by the 1880s[3].

2. Amid widespread concern about housing conditions in the capital, private housing charities and the newly formed London County Council started to demolish the worst housing and replace it with lower density accommodation. The overspill population was housed in new developments in the expanding suburbs within the County of London[4] or outside its borders in Kent, Essex and Middlesex.

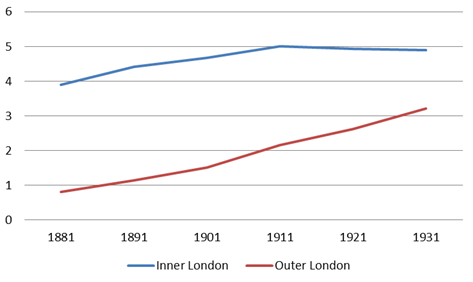

3. This policy of rehousing people from the densely populated inner city continued in the Inter-war period as did suburban development[5]. The result was that while the population in what is now known as Greater London[6] grew rapidly the population of Inner London actually fell from 1921 onwards. Figure 1 below shows London’s population between 1881 and 1931[7]

Figure 1: London’s population 1881-1931[8]

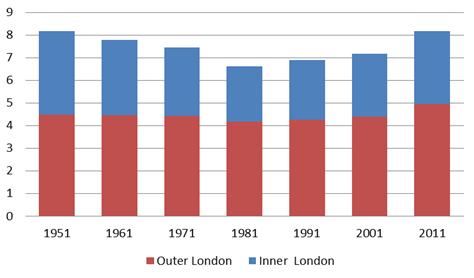

4. In 1951 London’s population’s was estimated at 8.2 million. Thirty years later, in 1981, it had fallen to 6.6 million. In the next thirty years it rose, returning to 8.2 million in 2011. London’s estimated population in June 2013 was 8.4 million[9]. The fall in population between 1951 and 1981 was predominately as a result of an intensification of the planning decision to rehouse people outside Inner London. The rise since then has been driven by increasing levels of immigration.

Figure 2: London’s population 1951-2011[10]

5. The planning decisions that shaped London in the decades after World War 2 were based on the Greater London Plan drawn up in 1944 by leading town planner, Sir Patrick Abercrombie. It covered the whole region from Luton to the north down to the Surrey/Sussex border in the south. It was felt that urban concentration led to public health and communication issues and that the decentralisation of industry and population from congested urban areas was the solution. It was recommended that there should be no new industrial development in London and the Home Counties and that 1.26 million people should be moved from Inner London to elsewhere in the region outside the city[11].

6. These recommendations were implemented. The New Towns Act of 1946 led to the building of Stevenage, Bracknell and Milton Keynes among other places. Other towns outside London were expanded to take some of the dispersed population. Within Inner London there was large scale redevelopment of housing stock which was considered to be of poor quality (or bomb damaged); this led to lower density neighbourhoods. As a result of these planning decisions the population of Inner London fell from 3.7 million in 1951 to 2.4 million in 1981 while the population of Outer London remained largely unchanged (see figure 2 above) during this period.

7. By the mid-1970s the Greater London Council was concerned over the loss of population and jobs in Inner London. In 1977 the Government announced a reduction in the target population of the new towns and the policy of population dispersal drew to an end.

8. Immigration is now the driver of population growth in London. In 1991 London’s population of 6.7 million consisted of 5.2 million who had been born in the UK and 1.5 million who had been born abroad. By 2011 London’s population had increased to 8.2 million but those born in the UK remained at 5.2 million while those born abroad had doubled to 3 million. This is illustrated in figure 3 below:

Figure 3: London’s population born in the UK and abroad

9. Even these figures disguise the true impact of immigration on London. The overall number of UK born in London may look relatively stable but the majority of births in the city were to parents who were both foreign born. Between 2001 and 2011 over 540,000 births in the city were to parents who were both foreign born compared to 505,000 to UK born parents and a further 260,000 where one parent was foreign born. Figure 3 below sets out the annual births in London. It shows that total births in London rose across this period, from 104,000 in 2001 to 132,800 in 2011. This rise came entirely from births where both parents were foreign born, which by 2011 made up 45% of all births in the city. This rise in annual births also has big implications for the number of primary school places needed in the near future.

Figure 4: Births in London to UK and Foreign born parents, 2001 to 2011

Housing

11. London’s immigrant population can be absorbed into its housing stock in three ways:

- more people can live in the same number of rooms

- new homes can be built to house the extra population

- by replacement of the existing population

All three have occurred in London.

a. Number of People per room

12. Some of the increased population in London has been accommodated by fitting in more people per room. There is wide variation in the family size of migrants and in the accommodation they occupy but as a whole the foreign born population has a larger family size[12]. The total fertility of a foreign born mother in London is 2.28 compared to an average of 1.78 for UK born mothers[13]. Some groups have much higher birth rates. For example, Somalia born mothers have an average of over 4 children while Bangladeshi born mothers have an average of over 3 children[14]. Also, migrants tend to live in more crowded conditions. Table 1 below shows the number of rooms per person where the Household Reference Person (HRP) was UK born and where the HRP was foreign born[15].

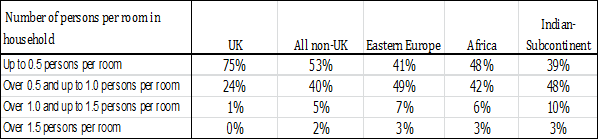

Table 1: Number of persons per room in households by country of birth, 2011[16]

13. Three-quarters of the households with a UK born Household Reference Person (HRP) had 0.5 persons per room or fewer. In contrast the majority of households where the HRP came from Eastern Europe, Africa or the Indian sub-continent had over 0.5 persons per room with a significant portion having over 1 person per room. These figures are for England and Wales as a whole; it is likely that the number of people per room is even greater in London. Separate analysis by the Office of National Statistics found that the five local authorities with the most households living in overcrowded conditions were all in London. In Newham over 25% of households lived in overcrowded conditions[17].

b. New Homes Built

14. Between 2001 and 2011 an additional 250,000 dwellings were added in London, an average rate of 25,000 a year[18]. Around 190,000 of these came from the construction of new homes[19] with the rest coming from the conversion of existing buildings into homes or houses into multiple flats. Over the same period the number of households in London was estimated to have increased by 250,000 (compared to a population increase of one million, see paragraph 1 above)[20]. At first glance this looks like enough accommodation has been built to accommodate the increased number of households, albeit in generally more crowded conditions. However, the large outward migration of existing residents from London to the rest of England must now be factored in.

15. Large numbers of UK residents both move to London from elsewhere in the UK and also leave London for elsewhere in the UK each year. However overall there has been a net loss of residents from the capital. Between 2001 and 2011 there was a net loss of 680,000 residents from London to elsewhere in England. The majority of these will be UK born. Given the average UK household size is 2.3 people[21] this would imply a net loss of around 290,000 households. Had there not been this net exodus from London then the additional households created between 2001 and 2011 would have been around 540,000 and the increase in dwellings would have covered only half of that increase.

c. Displacement

16. From the 1980s overall employment in the capital, which had been declining with the closure of the docks and the loss of manufacturing jobs started to increase[22]. In particular, London grew in importance as a financial and service centre. Policies to decant people from inner London to the outside the city had also come to an end (see paragraph 7). However, the net outflow of Londoners has continued.

17. A key constraint on the number of people that can live in London is the number of available dwellings. The more households that compete to live in the same number of dwellings, the more that are forced (or choose) to look outside the capital to find somewhere they can afford to live.

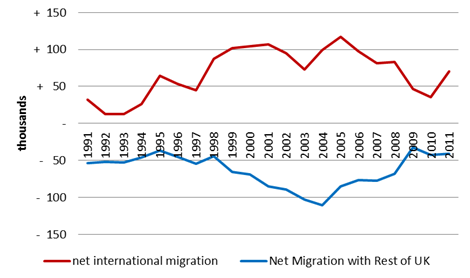

18. Research by Timothy Hatton and Massimiliano Tani found that, for the southern regions of England, for every 100 additional international migrants coming into the area there is a ‘displacement’ of 44 others to location elsewhere in the UK[23]. Research from the London School of Economics has demonstrated that the levels of international migration to the UK are mirrored by net internal migration out of London[24]. This is illustrated in figure 5 below:

Figure 5: London’s mirror image migration trends[25]

19. At the local authority level in London internal migration patterns have varied. The ONS have produced detailed information on internal migration between local authorities[26]. It allows for an analysis of residents moving between London and the rest of England as well as an analysis of residents moving within London to a different local authority.

20. Over the last ten years some of the Inner London boroughs that are in parts now gentrified have actually experienced a net infow of people from elsewhere in England (excluding other London boroughs), while losing a greater number of residents to Outer London. For example, Camden has gained around 15,000 residents from elsewhere in England (excluding other London boroughs) but has lost 30,000 residents.

21. Many of the Outer London boroughs have received an increase in residents moving from Inner London while losing a greater number of people who left for the rest of England. For example Croydon gained around 20,000 residents from the rest of London but lost around 30,000 to the rest of England.

22. Newham and Brent have lost population both to the rest of London and to people leaving London.

23. Nonetheless, regardless of the pattern of internal migration, in the last ten years every single London borough has lost residents through internal migration and has seen an increase in the foreign born population through international migration.

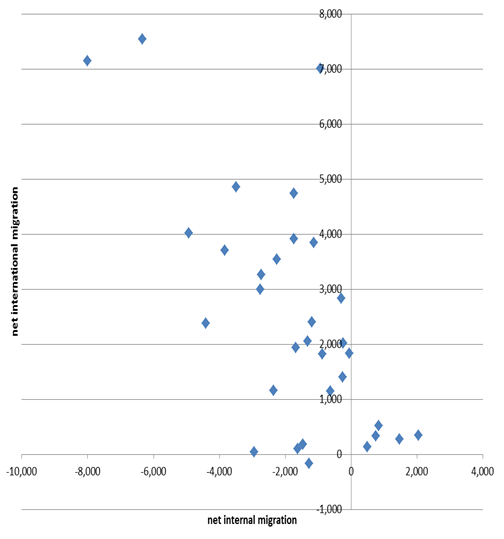

24. Figure 6 below shows the net change in both international migrants and internal migrants in the year ending June 2013 for London local authorities. There is a clear correlation between the increase in international migrants and the rise in the number of Londoners leaving with a co-efficient of -0.67. Similar results are found for other years.

Figure 6: Change in International Migrants and Internal migrants for London Local authorities, 2013[27].

Figures in thousands correlation co-efficient -0.67

d. Housing Tenure

25. The impact of the rapid rise in population on the housing stock can be seen by looking at the different housing tenures in London. London households live in a mix of owner-occupied, privately rented and social housing.

26. Social housing, managed by either a local authority or housing association makes up a significant portion of the housing stock. One third of all housing in Inner London is social housing and across the city as a whole one quarter of households live in social housing[28]. Social housing is rented to the tenant at rates well below market level and is hugely sought after by those on lower incomes. The numbers on local authority waiting lists more than doubled between 2000 and 2012 to around 380,000 households[29].

27. Traditionally social housing was allocated to those that had grown up in the local area. However, changes to housing policy such as the 1977 Homeless Persons Act meant that priority for social housing passed from those who had grown up in the area to those that were considered most in need - often immigrants. The bitter conflict over housing that resulted between Bangladeshis and white British residents is well documented by Michael Young in the ‘The New East End’.[30] Many of the white British who failed to get off the housing waiting list into social housing moved out to Essex instead.

28. Social Housing in London has now become mostly the preserve of the most disadvantaged. Despite the below market rents 560,000 households, or nearly three-quarters of all the households in social housing, receive housing benefit[31] and over half the households are solely reliant on state support for their income[32].

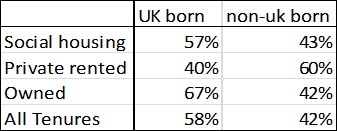

29. Half of social housing in Inner London is occupied by households with a foreign born household reference person (HRP) and the figure for the whole city is 43%[33] as table 2 illustrates.

Table 2: Tenure in London by UK born and non-UK born Household Reference Person

Non-UK born make up 42% of all households and 43% of all households in social housing. It is striking that the proportion of migrants who live in social housing is the same as the proportion of UK born households, despite the fact that many migrants will have arrived relatively recently[34].

30. The option for those excluded from social housing along with everyone else who cannot afford to buy a home is the private rented sector. The proportion and number of households living in the private rented sector has increased dramatically in recent years. This is also the tenure that the majority of migrants to London, at least initially, will live in. In 1991 around 15% London households lived in the private rented sector. This figure had increased to over 25% by 2011 (numerically it has more than doubled). The increase in population in search of property to rent has had a major impact on rental prices. The median private rent for a 3 bed flat in London is around £1650 per month, compared to £900 in the South East and even less in the East and South West[35].

31. Some of those in the private rented sector qualify for housing benefit (275,000 of around 900,000 households). Some reduce their rents by sharing with more people. However, other households will look outside London for cheaper properties.

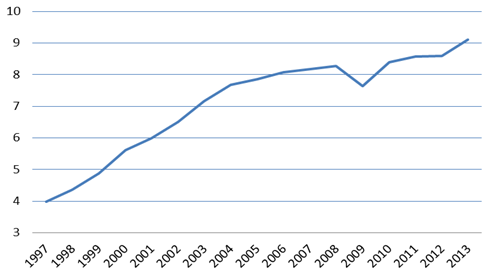

32. For those that aspire to own their property high rents make it harder to save for the deposit. In addition the increased demand for housing from a growing population has contributed to driving up house prices[36] with London having become increasing unaffordable in relation to earnings and in comparison to the surrounding areas of England. Figure 7 below shows the ratio of median house prices to earnings in London between 1997 and 2013. This ratio was around 4 in 1997 but by 2013 median house prices in London had increased to 9 times median earnings.

Figure 7: Ratio of median earnings to median house prices in London[37]

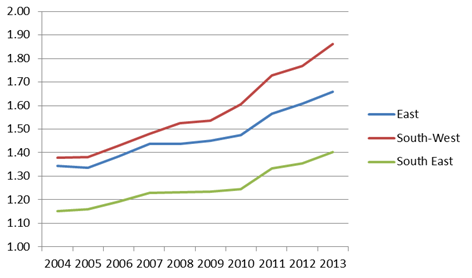

33. Figure 8 below shows the ratio of average house prices in London relative to other parts of Southern England. Prices in London have grown much more than in neighbouring regions in the last ten years.

Figure 8: London average house prices relative to regions of southern England[38]

34. Many who cannot afford to buy a house in London, yet nevertheless wish to own their own property, will choose to look outside London for their housing. In addition, some existing homeowners in London may take advantage of the price differential to sell up and buy elsewhere (this is the aspect that the BBC Home Editor Mark Easton claimed was the principal reason behind change in Barking & Dagenham, which he described as a success[39] ).

e. Cultural

35. Another aspect in the decision to leave London may be cultural, with those unhappy about the changing nature of their neighbourhoods opting to move. This would free up more housing for migrants and thus accelerate the rate of change in the area. As the majority of those leaving London have been of white British ethnicity researchers have examined whether ‘white flight’ is behind people leaving more ethnically diverse parts of London but have concluded that there is little evidence of attitudinal difference towards immigrants between those who leave London and those who stay[40]. However, they did find a preference among all ethnic groups for cultural similarity. For non-white ethnicities this means largely moving within London whereas for the white British this can mean changing districts within London but also moving out to other parts of the UK

London’s projected Population Growth

36. In 2014 London’s population is estimated to be 8.5 million[41] (up from the 2011 Census figure of 8.2 million). Projections from the ONS have London’s population continuing to grow rapidly, reaching 10 million in fifteen years’ time, an increase of 1.5 million on the current population.

37. The Mayor’s Housing Strategy recognises that the city’s population is rising rapidly and cites GLA figures that also project the population to hit 10 million by 2030. To cope with this rapid population growth London needs many more homes.

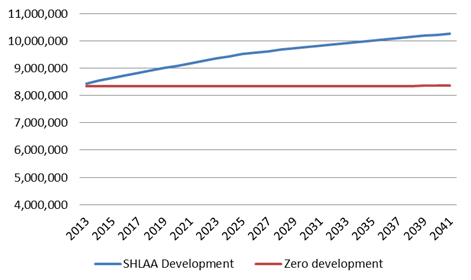

38. The constraints of housing supply on the projected population growth have been modelled in two GLA projections out to 2041[42]. One population projection is based on being able to develop new housing[43] on all the land identified in London’s Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA)[44]. The second population projection is modelled under a scenario where there is no future house building (i.e. zero development of dwellings). Both projections are calculated using the same level of international immigration.

39. The SHLAA projection produces a population that continues to grow rapidly. The zero development projections gives no population growth. This is shown in figure 9 below.

Figure 9: GLA London Population projections constrained by housing development

An additional 1.6 million people leave London in the Zero-development projection than in the SHLAA development[45].

40. The zero development scenario is an extreme scenario that will not happen as some development of housing is bound to occur. However, it further illustrates the central point; the more that housing supply fails to keep up with population growth the greater the number of households that will have to leave London and live elsewhere.

41. The Mayor’s Housing Strategy recognises that the shortage of housing has pushed up prices and rents. The Housing Strategy estimates that the projected population growth to 10 million will create 40,000 new households a year, more than double the rate of growth of the existing supply. To cope with this increase and to tackle existing backlogs the Mayor aims to facilitate the building of 42,000 more homes per year over the next decade and beyond.

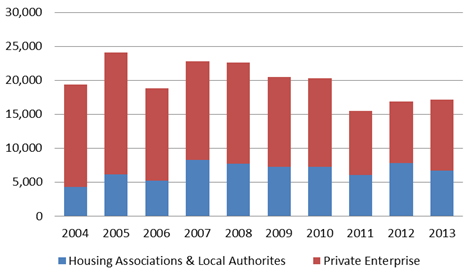

42. In the last decade the average number of homes completed in London was 18,000 as illustrated in figure 10 below[46]:

Figure 10: Dwellings completed mid-2004 to mid-2013

43. Given the historical record of home building in the capital the Mayor’s target could be viewed as optimistic. Nevertheless, the Mayor’s Housing strategy includes a range of measures both to free up brownfield sites and to improve the financing of new construction. It has also set out the need for more homes for those on ‘intermediate’ salaries who currently find themselves excluded from social housing yet unable to afford home ownership.

44. However, the Housing Strategy misrepresents the reason for this projected population growth claiming that it is “primarily the natural growth that results from London’s relatively youthful population”[47]. The projected growth, like the growth experienced from 1991, is down to international immigration - both directly from the immigrants themselves and indirectly from their future children.

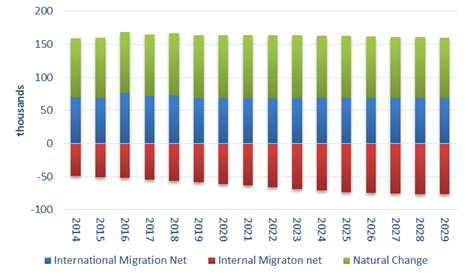

45. Between 2014 and 2029 the ONS project net international immigration into London of 1.1 million. However, this will be offset by just over 1 million people projected to leave London for the rest of England. The natural change comes from an increase of births over deaths, the high level of births being driven by the immigrant population already here and those immigrants yet to arrive. In 2012 only one third of all births in London were to parents who were both UK born[48](see also paragraph 9 above). Figure 11 below shows the breakdown of the components of the population growth in London[49].

Figure 11: Components of projected population growth in London

46. Figure 10 highlights the other important aspect that is often ignored in discussions on London’s growth, namely that the population projection of 10 million relies on a continued net outflow of London residents to the rest of England of some 50 -70,000 a year.

47. Without over one million people leaving London in the next fifteen years London’s population would reach 11 million or more. Plans to accommodate London’s population assume that this outflow will continue so households will be displaced to the rest of the England with considerable implications for other regions of England.

Conclusion

48. London’s growing population is driven by mass immigration. This population growth not only makes the city more crowded but, as this paper has shown, due to the resulting pressures on its housing supply it has also displaced people from the capital. Those who promote the idea of an “international city” effectively free of constraints on immigration seem to be blind to the implications for the existing population of London. They should be clear that the result will be more Londoners forced to leave the city and find somewhere else to live. Are they content with that outcome? It is not enough to simply say “build more homes”. The Mayor already has ambitious plans to double homebuilding yet this still relies on a continuing net outflow from the City.

49. Of course, it is important that London continues to attract skilled migrants but this cannot be limitless. There has so far been little public debate about the desirability of London’s population growing so rapidly. It is time for the impact on Londoners and their housing needs to be considered alongside the calls for ever more immigration from the business lobby.

Footnotes

- The total fertility rate in the late 19th century was over 5

- Census of 1881, England and Wales, Vol.IV General Report, page 51 http://www.histpop.org/ohpr/servlet/Show?page=Home

- Stephen Inwood, “City Of Cities: The Birth Of Modern London” (2005, Macmillan)

- The boundaries of the County of London were created by the 1888 Local Government Act and roughly corresponded to the area known today as Inner London.

- See for example the LCC redevelopment of Poplar and surrounding districts http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=46467

- Greater London was formally created by the 1963 local government act.

- Show 43 more...

- The total fertility rate in the late 19th century was over 5

- Census of 1881, England and Wales, Vol.IV General Report, page 51 http://www.histpop.org/ohpr/servlet/Show?page=Home

- Stephen Inwood, “City Of Cities: The Birth Of Modern London” (2005, Macmillan)

- The boundaries of the County of London were created by the 1888 Local Government Act and roughly corresponded to the area known today as Inner London.

- See for example the LCC redevelopment of Poplar and surrounding districts http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=46467

- Greater London was formally created by the 1963 local government act.

- A Vision of Britain through time http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/place/1

- Inner London covers the boroughs of Camden, Greenwich, Hackney, Hammersmith & Fulham, Islington, Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea, Lambeth, Lewisham, Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Wandsworth, Westminster

- Office of National Statistics

- A Vision of Britain Through Time, http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/data_cube_page.jsp?data_theme=T… P&u_id=10202620&c_id=10001043&add=N

- The Changing City: Population, Employment and Land Use Change since the 1943 County of London Plan, Prof James Simmie, Corporation of London, 2002 http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/business/economic-research-and-inf… nts/2007-2000/The-Changing-City.pdf

- completed family size is implied by the current birth rates

- Childbearing Among UK Born and Non-UK Born Women Living in the UK, Office of National Statistics http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171766_283876.pdf

- 2011 Census Analysis, Babies born in England to non-Uk born mothers infographic http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/fertility-analysis/childbearing-of-… info-mother-s-country-of-birth.html

- Household Reference Person is essentially the ‘Head of the Household’. It is: • the member of the household in whose name the accommodation is owned or rented, or is otherwise responsible for the accommodation. In households with a sole householder that person is the household reference person • In households with joint householders the person with the highest income is taken as the household reference person. • If both householders have exactly the same income, the older is taken as the household reference person.

- 2011 Census Analysis, How do Living Arrangements, Family Type and Family Size Vary in England and Wales?, Office of National Statistics, Table CT0149 http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-362556 Eastern Europe consists of the EU accession countries since 2001.

- 2011 Census Analysis, Overcrowding and under-occupation in England and Wales http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census-analysis/overcro… ccupation-in-england-and-wales.html Overcrowding definition is based on the bedroom standard. The Housing (Overcrowding) Bill of 2003 defines the bedroom standard as: “(4) For the purposes of the bedroom standard a separate bedroom shall be allocated to the following persons— (a) A person living together with another as husband and wife (whether that other person is of the same sex or the opposite sex) (b) A person aged 21 years or more (c) Two persons of the same sex aged 10 years to 20 years (d) Two persons (whether of the same sex or not) aged less than 10 years (e) Two persons of the same sex where one person is aged between 10 years and 20 years and the other is aged less than 10 years (f) Any person aged under 21 years in any case where he or she cannot be paired with another occupier of the dwelling so as to fall within (c), (d) or (e) above.”

- Department of Communities and Local Government, table 125: Dwelling Stock estimates by local authority district https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-dwelling-stock-including-vacants

- DCLG Housing Statistics, Table 253 permanent dwellings started and completed by district https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-house-building

- Department of Communities and Local Government, table 406: Household Projections by District, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-household-projections

- 2011 Census Analysis, Population and Household Estimates for the United Kingdom, March 2011, Office of National Statistics http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census/population-estim… -the-united-kingdom-march-2011.html

- The Changing City: Population, Employment and Land Use Change since the 1943 County of London Plan, Prof James Simmie, Corporation of London, 2002 http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/business/economic-research-and-inf… nts/2007-2000/The-Changing-City.pdf

- Hatton, T. J. and Tani, M. (2005), Immigration and Inter-Regional Mobility in the UK, 1982–2000. The Economic Journal, 115: F342–F358

- Ian Gordon, Densification, Development and/or Displacement: accommodating migrant-induced population growth in London (and its extended region), LSE/HEIFS conference, 24th March 2014 http://lselondonmigration.org/2014/03/24/how-is-london-being-transformed-by-migration/

- International migration to London region taken from ONS Long Term International Migration table 2.06 and 2.11. Internal migration data from 2001 onwards http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/migration1/internal-migration-by-lo… ies-in-england-and-wales/index.html Earlier internal migration data provided through correspondence with the ONS.

- Ibid

- Components of Population Change by local authority, Office of National Statistics, http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-322718

- ONS 2011 Census data on tenure

- http://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/7.15

- The New East End, Kinship, Race and Conflict, Geoff Dench, Kate Gavron, Michael Young, 2006

- Housing Benefit Caseload, DWP, https://sw.stat-xplore.dwp.gov.uk/webapi/jsf/dataCatalogueExplorer.xhtml

- Homes for London, The London Housing Strategy, April 2014, page 34 https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Draft%20London%20Ho… ing%20Strategy%20April%202014_0.pdf

- 2011 Census analysis, Tenure by country of birth for London, table CT0186-2011 http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/about-ons/business-transparency/freedom… oc-data/census/migration/index.html

- 2011 Census Analysis, Tenure by year of arrival in UK – London Region http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/about-ons/business-transparency/freedom… oc-data/census/migration/index.html

- Private Rental Market Statistics www.voa.gov.uk/corporate/statisticalReleases/140610_Private_Rental_Market.html

- House prices are partly determined by the availability of credit but a key component of prices in London has been the shortage of supply in relation to the growing demand from the growing population. For further reading see http://www.uk-houseprices.co.uk/housing_market/factors_affecting_prices.html and; Reshaping housing tenure in the UK: the role of buy-to-let http://www.imla.org.uk/perch/resources/imla-reshaping-housing-ten… the-role-of-buy-to-let-may-2014.pdf

- Ratio of house prices to earnings

- House Price Index (HPI), table 11, ONS http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-333226

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-21511904

- White Exit and how to stop it, Eric Kaufmann, http://www.demos.co.uk/files/mapping_integration_-_web.pdf?1397039405

- ONS sub-national population projections http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-335242

- GLA 2013 round population and household projections http://data.london.gov.uk/datastore/package/gla-2013-round-population-and-household-projections

- This projection allows for around 40,000 dwellings a year to be developed out to 2025, followed by 26,000 dwellings year to 2031 and 20,000 dwellings a year out to 2041.

- The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2013 http://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/FALP%20SHLAA%202013.pdf

- The GLA calculated outflows for the population as a whole and has not produced separate values for international and internal outflows in these two projections.

- DCLG Housing Statistics, Table 253 permanent dwellings started and completed by district https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-house-building

- Homes for London, The London Housing Strategy, April 2014 https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Draft%20London%20Ho… ing%20Strategy%20April%202014_0.pdf

- Written Parliamentary Question from Nicholas Soames MP, HC Deb, 10 December 2013, c188W

- Subnational Population Projections, 2012-based Projections, Office of National Statistics Table 5 http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-335242