The Conservative Performance on Immigration Since 2010

12 February, 2015

1. Summary

1.1 The net migration target was sensible at the time and proved a valuable focus for policy. There was a significant reduction in non EU migration but this was largely counterbalanced by an increase in EU migration. Policy focussed on tightening conditions for entry. The quality of economic migration was improved but the numbers were largely unaffected and the cap on Tier 2 was never reached. Squeezing out bogus students was a major success but there is scope for further action. The impact of measures taken to limit family migration has been mixed. The Conservatives failed to increase outflows which had been flat during the previous government and remained so into this one, despite a substantial increase in arrivals. The outflow of British citizens remained broadly unchanged. Ensuring migrants, particularly students, depart when their visas expire must be the next focus for policy action but real progress will undoubtedly require a significant increase in resources. Conclusions can be found at paragraph 13.

2. Introduction

2.1. The Conservatives are well short of their target of net migration in the “tens of thousands” by the end of this Parliament. The latest figure (up to the second quarter of 2014) was 260,000.

2.2. This paper considers three questions:

- Was the concept wrong?

- Was the execution at fault?

- What lessons can be drawn?

3. The concept of a target

3.1. The target based on overall net migration has been criticised on the grounds that it included two elements – British and EU migration – which were not under the government’s control. However, these two elements had cancelled each other out in all but two of the previous 18 years.

3.2. When the target was selected by the Conservatives the latest figure for overall net migration was 166,000 (in the year to mid-2009); therefore a target of below 100,000 over the course of a Parliament seemed a reasonable ambition. The estimate of net migration for the year ending mid-2009 was later revised up to 205,000 when the ONS realised that they had undercounted East European migration.[1]

3.3. There is no doubt that the existence of a target, especially one to which the government was committed at the highest level, was extremely valuable in focussing the efforts of the many government departments with an interest in the immigration debate. With hindsight, however, a target confined to non-EU migration would have avoided the risk of a very rapid increase of EU migration such as, in fact, occurred when it doubled between June 2012 and June 2014.

4. The execution of the policy

4.1. Action was framed by the Conservative manifesto as modified by the Coalition Agreement, with the Civil Service being guided by the latter. It is noteworthy that the Coalition Agreement did not include a commitment to reduce net migration to the tens of thousands. This somewhat weakened the hand of those in government who were pressing for effective measures.

5. 2010 Conservative Manifesto and pre-election promises

5.1 The 2010 Conservative manifesto made a strong commitment to reducing the level of migration to the UK. Published on April 13th 2010, the manifesto stated that a Conservative government would ‘take steps to take net migration back to the levels of the 1990s- tens of thousands a year, not hundreds of thousands.’[2] In specifics, the manifesto pledged to:

- Set an annual limit on the number of non-EU economic migrants admitted into the UK to live and work.

- Access limited to those who would bring the most value to the British economy.

- Apply transitional controls as matter of course for all new EU member states.

- Introduce an English language test for anyone coming to the UK to get married.

- Promote integration.

- Strengthen the system of granting student visas so that it is less open to abuse.

- The manifesto made several specific pledges on student migration:

- That foreign students at new or unregistered institutions would pay a bond in order to study in the UK, to be refunded at the end of their studies.

- Ensure that foreign students actually had the funds to support themselves while in the UK.

- Require that students leave the country and reapply if they switched to another course or applied for a work permit.

6. The Coalition Agreement

6.1. The Coalition Agreement, worked out with the Liberal Democrats and announced on May 20th 2010, contained the following pledges on immigration:

- An annual limit on the number of non-EU economic migrants admitted to the UK to live and work.

- A commitment to ending the detention of child migrants. (Fulfilled by the Immigration Act 2014).

- The creation of a dedicated Border Police Force. (This was established in March 2012).

- The reintroduction of exit checks and support for E-borders.

- Introduction of measures to minimise abuse of the immigration system, for example via student routes, and human trafficking to be a priority. (See below).

- Exploration of new ways to improve the current asylum system to speed up the processing of applications.

7. Work Migration

(a) Work Policy Changes

7.1. In July 2010 a temporary cap on Tier 2 (General) was introduced. In April 2011 this interim cap was made permanent, set at 20,700 a year. The cap excluded Tier 2 (Intra Company Transfers) and those applying to switch into Tier 2 (General) who were already in the UK. While the Tier 2 (ICT) visa was excluded from the annual cap the visa conditions were tightened; the salary threshold was raised and the right to settle was removed.

7.2 In December 2010 the government closed the Tier 1 (General) route to overseas applicants. The visa which was intended for highly skilled migrants to come to the UK without a job offer was closed to all applicants in April 2011.

7.3 In February 2012 it was announced that the automatic right of economic migrants to settle after five years would end and that a salary threshold of £35,000 per year would be required to qualify for settlement.

(b) Impact of Changes

7.4. Policy has had little impact on the numbers of non-EU work migrants. The cap on Tier 2 migration has not been reached and any reduction resulting from the closure of Tier 1 has been cancelled out by a more general rise in work visas as the economy has recovered.

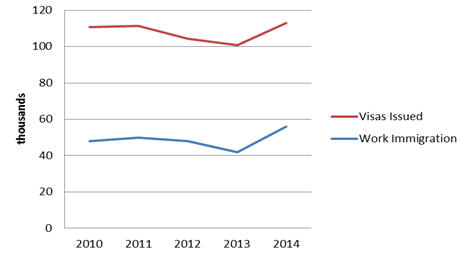

Figure 1: Work visas and Immigration June 2010 to June 2014

7.5. There may be a small reduction in non-EU net migration for work as the salary threshold required for settlement begins to take effect, as it should have the effect of increasing the outflow of workers.

8. Student Policy changes

(a) Students

8.1. The government undertook significant reform of the Tier 4 (General) visa which had been abused on a significant scale.[3]

8.2. The right to work while studying on a Tier 4 visa was restricted to those studying at publicly funded education establishments and the number of hours that could be worked was dependent on the level of study. Those studying at private colleges were restricted from working altogether. The government also tightened the language requirement that applicants had to satisfy in order to be granted a visa, raising it from A2 to B1. Universities were, however, exempted from language requirements on the grounds that they were best placed to decide the language competence and requirements of their students. The right to bring dependants to the UK was also restricted to those studying at Masters level and above for a minimum of one year. Those studying at Bachelors level and below were not entitled to bring their dependants with them. Finally, in order to extend a Tier 4 visa, students had to demonstrate academic progression - ensuring that students could no longer continue studying at a low level on an extended student visa in order to remain in the UK.

8.3. Following a pilot scheme which suggested that significant abuse continued to take place in certain parts of the world, interviews (which had been abolished in 2008) were reintroduced for students in 2012.[4]

8.4. In April 2012 the government closed Tier 1 (Post Study Work) to new applicants. The visa had allowed students to remain in the UK to find work for two years with no restrictions.

8.5. Reforms were also carried out to ensure that only genuine education establishments could sponsor visas. All sponsors were required to meet more rigorous Highly Trusted Sponsor requirements.

(b) Impact of Changes

8.6. There has been significant success in this field. The government’s reforms have led to the closure of over 700 bogus colleges which existed to make money through facilitating immigration.

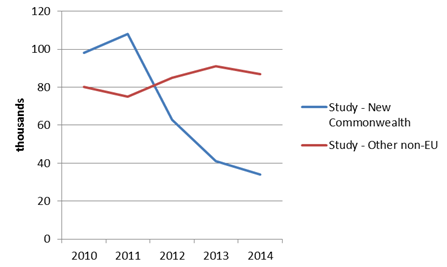

8.7. There has been a large reduction in student immigration from the New Commonwealth. Student numbers from elsewhere outside the EU have actually risen slightly, crucially from China. Overall, there was a reduction in immigration for study of just over 50,000. This reduction occurred in the further education sector, where the majority of the abuse had been taking place. The university sector has experienced an increase in applications of 17% since 2010 and the total number of non-EU students studying at Universities has increased by 4% since the academic year 2010/11 to 310,200 in 2013/14.[5]

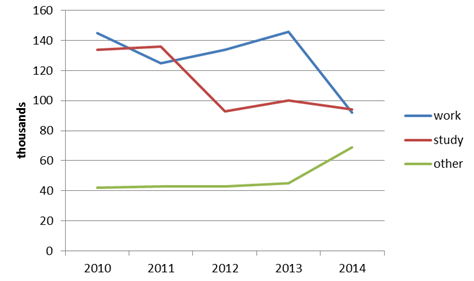

Figure 2: Study Immigration June 2010 to June 2014

8.8. Any further reduction in net migration of students is highly dependent on ensuring that students depart the UK when their visa expires. The ONS has only recently started collecting data on student outflows and the numbers show that 50,000 students have departed in recent years, suggesting that students are departing at around the third of the rate that they arrive and are therefore a significant source of overstaying. Rates of overstaying should diminish as interviews ensure a more compliant student intake.

9. Family

(a) Family Policy Changes

9.1. The government has made some significant changes to the family migration route.

9.2. In 2012 a minimum income threshold of £18,600 was introduced for a British citizen who wished to sponsor a partner, a higher income threshold was introduced for those with children: £22,400 for a partner and one child and an additional £2,400 for each further child. The threshold could include both savings and income from employment. However the prospective earning potential of the migrant could not be included.

9.3. The probationary period that a partner had to wait before applying for settlement was increased from two years to five years. The ability to apply for immediate settlement which was previously available to those living together overseas for four years was abolished.

9.4. Adult/elderly dependent relatives are now required to apply from outside the UK, be a close relative and demonstrate that, as a result of illness or disability, they require long-term personal care to perform everyday tasks and this care can only be provided in the UK by their sponsor and without recourse to public funds.

(b) Impact of Changes

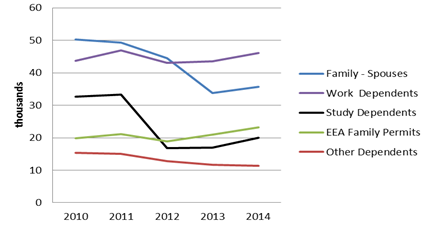

9.5. The impact of family reforms has been to reduce the number of visas issued to spouses as well as the dependants of work and study migrants. EEA family permits which allow EEA migrants to bring in a non-EEA spouse to the UK have increased; applicants for EEA family permits do not have to meet the income threshold imposed on British nationals.

Figure 3: Spouse and Dependant visas issued June 2010 to June 2014

10. The Immigration Act 2014

(a) Policy Changes

10.1 The 2014 Act was arguably the Government’s flagship piece of immigration legislation. The Act was far reaching in its scope and was specifically designed to create a ‘hostile environment’ for illegal immigrants. The legislation introduced the following changes:

- Cuts the number of immigration decisions that can be appealed in the courts from 17 to 4.

- Requires that the courts have regard to the “public interest” as set out in Article 8.2 of the Human Rights Act when considering immigration decisions that might breach an individual’s human rights under that Act. This essentially requires the courts to give due weight to the public interests that exist in the legislation including national security, public safety, the economic wellbeing of the country, the prevention of disorder or crime, the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedom of others.

- Extends the notice period for couples wishing to marry or enter a civil partnership from 15 days to 28 days thus strengthening the ability to disrupt and prevent sham marriages.

- Requires private landlords to conduct checks on the immigration status of new tenants and introduces a civil penalty for those landlords that rent to illegal immigrants without carrying out checks. .

- Introduces a framework for charging temporary migrants (those without Indefinite Leave to Remain) an annual health levy to contribute towards NHS provision. This provision has not yet been introduced.

- Restricts the right to obtain a UK driving licence to only those non-EEA nationals who have a minimum of six months leave to remain in the UK, preventing illegal immigrants from accessing a driving licence (which are used by many people to establish identity for the purposes of banking, accommodation, utility bills etc.) The Act also provides for the revocation of the licences of those individuals with no legal right to remain in the UK.

- Requires that banks and building societies check a Home Office list of disqualified persons before they allow an individual to open a new current account or be added to an existing current account, a disqualified person being someone in the UK who has no legal right to remain.

(b) Impact of Changes

10.2 There is little evidence that the Act has thus far had any impact on numbers. Many of its provisions are yet to be, or have only recently been, implemented.

11. Asylum

(a) Policy Changes

11.1. The government has not undertaken significant change to the asylum system. The asylum system is largely administered by UK Visas and Immigration, one of the three divisions of the Home Office created following the abolition of the UK Border Agency. Removal of asylum seekers who have failed in their claim and have not departed is dealt with by the Immigration Enforcement division.

11.2. The Immigration Act 2014 maintained various protections for those seeking asylum. Part 2 of the Immigration Act removes the right to appeal an immigration decision with the exception of appeals on the grounds of asylum and human rights. Part 3 of the Act introduced a health levy for those subject to immigration control however the Act excludes those seeking asylum and protects the right of asylum seekers to access NHS services free at the point of access.[6]

11.3. In January 2014 the government introduced the “Vulnerable Person Relocation Scheme” to resettle vulnerable refugees from Syria. By September 2014 the scheme had allowed for the resettlement of 90 people.

(b) Impact of Changes

11.4. The resettlement of Syrian refugees is unlikely to have made any significant impact on numbers, which have remained relatively low throughout the time of this government.

11.5. The government has, however, failed to administer the system as effectively as it could and has allowed a backlog of new cases to build as it has sought to tackle the larger problem of a backlog of legacy asylum cases. The latest figures show that there remains a backlog of just over 21,000 asylum cases in the ‘Live Asylum Cohort’ which are cases that pre-date 2007 and require a decision.[7] There are also an additional almost 17,000 cases waiting an initial decision.[8]

12. What lessons can be drawn?

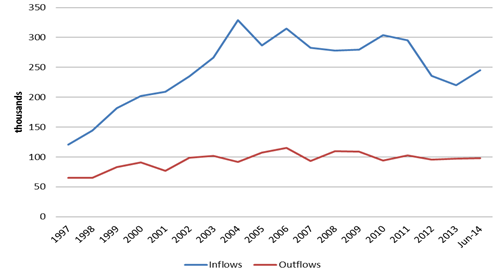

12.1. While the government failed to reduce net migration to the level that was promised in the Conservative manifesto it is undoubtedly the case that had the government not taken the measures outlined above net migration would currently be higher. The inflow of non-EU migrants has started to fall but there has been virtually no increase in outflows despite a substantial increase in inflows since 1997. In future, policy will have to focus on the outflow of migrants (students in particular), extensions and the failure to remove those with no leave to remain. There will also have to be much more effective action against employers of illegal workers, including full enforcement of fines.

(a) Departures

12.2. The central problem is that non-EU inflow rose sharply from 120,000 in 1997, to a peak of 330,000 (in 2004) to the present level of 245,000 – yet outflows have remained at around 100,000.

Figure 4: Non-EU Inflow and Outflow (IPS) 1997- June 2014

(b) Extensions

12.3. One explanation for the low rate of departure is the significant number of extensions granted annually.

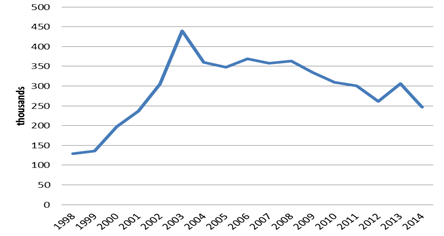

Figure 5: Grant of Further Leave to Remain1998-2014

12.4. Overall, grants of extension have fallen by 70,000 from 320,000 in 2010 to 250,000 in 2014. Extensions of both study and work visas have fallen The fall in work extensions occurred in the last year and is principally as a result of closure of the Tier 1 (General) and Tier 1 (Post-Study Work) categories.

12.5. ‘Other’ grants of extension rose to over 60,000 a year. Some of these grants labelled ‘Other’ in figure 6 below relate to extensions of spouse visas but the majority are granted under claims of family life, private life or on some other discretionary basis to those who were here illegally.

Figure 6: Grants of Extensions June 2010 to June 2014

(c) Enforced Removals

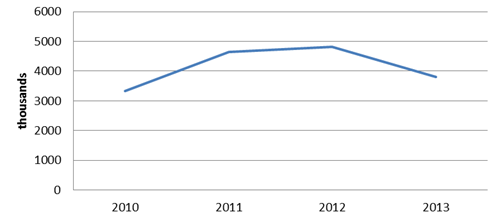

12.6 By contrast, the scale of enforced removals has been low – of the order of 4,000 - 5,000 per year as shown below:

Figure 7: Immigration offenders removed 2006-2013

(d) Re-organisation of the Home Office

12.7. There has been a major re-organisation of the Home Office since 2010; including the abolition of the UK Border Agency. These restructurings have inevitably impacted on the Home Office’s ability to implement the government’s policy changes. According to the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration’s reports, the Home Office has structural and organisational problems; although many of these problems pre-date this government. There is clearly scope for much more effective operation as the system settles down.

(e) Implementation

12.8 While the government has implemented some necessary and important reforms in terms of both rules and legislation, the implementation of existing rules and legislation at its disposal has not always been effective. The Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration has highlighted this failure on various occasions and the implications can be considerable. For example, a recent report by the Chief Inspector found that the Home Office was not carrying out the necessary background checks (required by law) on individuals applying for British citizenship and that consequently nationality was granted to individuals that did not meet the ‘good character’ requirement.[9] The wider issue is of course the growing (and perhaps impossible) demands placed on Home Office staff to ensure that the requirements of an ever increasing body of detailed legislation are complied with at a time of cuts in public expenditure.

(f) Funding

12.9. The total budget for immigration control in 2014/15 was £1.8 billion[10]. This is around 0.25% of the total government expenditure of £700 billion. This is clearly inadequate given the scale of the problem and the depth of public concern.

12.10 Underfunding is one of the primary reasons why the Home Office has been unable to address the very large backlog of cases that it inherited from the previous government. This amounted to around 368,100 even after the latter’s “backlog clearance exercises” which involved granting Indefinite Leave to Remain to those otherwise not entitled to it. There is at present a backlog made up of 26,300 cases known as the ‘Live Cohort’ which is made up of largely asylum cases (but also some immigration cases) which pre-date 2007 and are yet to receive a decision, a ‘Migration Refusal Pool’ of 173,500 cases whereby an applicant already in the UK has applied for a visa but has been denied yet has not left the country, as well as an additional 168,300 overstaying cases that the Chief Inspector has identified which pre-date 2008 and which are to be added to the existing Migration Refusal Pool. The backlog inherited by this government therefore totals 368,100.

12.11. There are also an additional 140,600 more recent live immigration cases that the Home Office describes as work in progress. Similarly, there are 17,000 new asylum cases awaiting a decision.[11]

(g) Data and Evidence

12.12. The Home Office has faced a chronic problem of a lack of data and management information. Without exit checks it has been unable to identify, let alone pursue, those that have overstayed their visa. This has resulted in a lack of evidence about who is overstaying and their routes of entry. It has also weakened the ability of the Home Office to demonstrate publicly where the abuse has been taking place.

13. Conclusions

13.1. The concept of a target for net migration was the right approach as it has focused both public attention and government efforts. In future, however, it would be more appropriate for a government target to focus on those elements that it can directly influence and therefore be expressed in terms of non-EU migration. The scale of EU migration remains a serious problem. As is well known, current EU obligations make it very difficult to mitigate. Renegotiation of these obligations will be essential after the coming election.

13.2. The execution, in terms of policy formation, was well focussed and on the right lines. More time is needed for the measures to take effect and there is much work to be done to tackle the issue of low outflows. In 2010 nobody had quite understood the extent of the chaos in the system so it has proved much more difficult than anticipated to bring the numbers under control.

13.3. The major lessons to be learnt include:

- The importance of departure. There has clearly been overstaying on a very substantial scale, especially by students who comprise 60% of the intake. It is unfortunate that the universities have failed to distinguish themselves from colleges where most of the abuse has taken place.

- Linked to this is the failure to remove more than a trivial number of overstayers; this seriously undermines the credibility of the entire system.

- The decision not to proceed with Identity Cards might also have played an important role as it removed a significant deterrent to overstaying.

- There needs to be more focus on implementation rather than on new legislation.

- That said, an exercise in consolidation of the immigration and asylum laws (without wholesale change) would be a useful aid to implementation.

- Finally, while there is much to be done to improve the productivity of the system, it is clear that the very limited resources devoted to immigration are seriously out of kilter with the very serious consequences for our society of continued mass immigration and the associated level of public concern.

13.4. There are also some wider matters which will continue to pose difficulties for an effective immigration policy. They include:

- The effect of coalition government. This was certainly a brake on effective action during the present Parliament and might well arise again.

- The pro-immigration bias of parts of the Civil Service (notably The Treasury), perhaps linked to a reluctance to tackle a sensitive subject.

- Continued Treasury enthusiasm for GDP growth, irrespective of the impact of immigration on population growth and on the lower paid.

- The influence of economic liberals, reinforced by pressure from some companies, motivated by their wish to be at liberty to import foreign labour, without always having a proper appreciation of the pressures placed on social services by large scale immigration

- A strong bias in the BBC in favour of immigration, combined with a reluctance even to address the case for reducing immigration.

- The large number of immigration lawyers, few of whom have any interest in immigration control. The result can be an unequal contest between a qualified lawyer and a relatively junior civil servant.

13.5. The foregoing is, of course, a natural part of a free and open society. However, it has led to a situation which is far from satisfactory to a large proportion of the electorate. The risk is that continued failure to control immigration might eventually undermine the credibility of successive governments and, indeed, of the political system as a whole.

Footnotes

- See Migration Watch UK Briefing Paper 9.32 ‘The case for revising the immigration figures‘, July 2013, URL: http://www.migrationwatchuk.co.uk/briefing-paper/9.32

- 2010 Conservative Manifesto, ‘An Invitation to join Government’, URL: https://www.conservatives.com/~/media/files/activist%20centre/pre… d%20policy/manifestos/manifesto2010, p. 21.

- See the National Audit Office, Immigration: The Points Based System – Student Route, March 2012, URL: http://www.nao.org.uk//idoc.ashx?docId=0f549a94-58b6-4080-8a93-fb6aa9bb4b5e&version=-1

- Home Office, Tier 4 Student Credibility Pilot: Analysis of Quantitative and Qualitative Data, Occasional Paper 104, July 2012, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/115920/occ104.pdf

- See HESA, URL: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/dox/pressOffice/sfr210/071277_student_sfr210_1314_table_9.xlsx

- The Immigration Act 2014, URL: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/22/contents/enacted

- Show 5 more...

- See Migration Watch UK Briefing Paper 9.32 ‘The case for revising the immigration figures‘, July 2013, URL: http://www.migrationwatchuk.co.uk/briefing-paper/9.32

- 2010 Conservative Manifesto, ‘An Invitation to join Government’, URL: https://www.conservatives.com/~/media/files/activist%20centre/pre… d%20policy/manifestos/manifesto2010, p. 21.

- See the National Audit Office, Immigration: The Points Based System – Student Route, March 2012, URL: http://www.nao.org.uk//idoc.ashx?docId=0f549a94-58b6-4080-8a93-fb6aa9bb4b5e&version=-1

- Home Office, Tier 4 Student Credibility Pilot: Analysis of Quantitative and Qualitative Data, Occasional Paper 104, July 2012, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/115920/occ104.pdf

- See HESA, URL: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/dox/pressOffice/sfr210/071277_student_sfr210_1314_table_9.xlsx

- The Immigration Act 2014, URL: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/22/contents/enacted

- See Table OLCU_2: Breakdown of the status of the OLCU 41k Cohort of pre March 2007 unconcluded people previously owned by Case Resolution Directorate (CRD) 1,2,5,11,15 of Asylum Transparency Data: November 2014, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_d… sylum_transparency_data_q3_2014.ods

- See Table ASY_3: Asylum work in progress of Asylum Transparency Data: November 2014, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_d… sylum_transparency_data_q3_2014.ods

- Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, An Inspection of Nationality Casework, April-May 2014, URL: http://icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Nationality-Report-web.pdf

- See National Audit Office, ‘Reforming the UK border and immigration system, July 2014, URL: http://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Reforming-the-UK-border-and-immigration-system.pdf and the Public Accounts Committee 31st Report on Border Force, December 2013, URL: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmpubacc/663/663.pdf

- See the Migration Transparency Data released 28 November 2014, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/migration-transparency-data and the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, ‘An Inspection of Overstayers: How the Home Office handles the cases of individuals with no right to stay in the UK’, May – June 2014, URL: http://icinspector.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Overstayers-Report-FINAL-web.pdf