Likely consequences of the MAC’s proposed immigration policy

16 October, 2018

Summary

1. The government are considering immigration proposals from the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) that would expose millions of jobs currently held by UK workers to new or increased competition from a huge pool of overseas candidates. As it has been recommended that the current work permit limit be scrapped, this risks a very significant rise in immigration at a time when voters are clear that they want a significant reduction. There would indeed be a strong incentive for overseas workers to take up such jobs since the work route offers a direct route to permanent settlement. Meanwhile, employers would be encouraged to recruit from overseas because they would likely be able to find more experienced workers at the likely £30,000 salary threshold than they would be able to find among UK workers at the same level of pay. A significant, and unlimited, inflow of workers from much poorer countries would put added strain on social cohesion at a time when 78% of Britons in areas that have experienced large-scale migration believe immigration has made their communities more divided.

Introduction

2. The government are in the process of considering the recommendations of the MAC published on 18 September.[1] These proposals would involve expanding the work permit system to EU workers, abolishing the cap on numbers and reducing the skill level required, from degree level to ‘A-level’. The present requirement to first seek a recruit in the domestic labour market could also be abolished. These changes would greatly widen the scope of the existing scheme.

a) Proposal to abolish the Tier 2 cap

3. The MAC has proposed abolishing the cap of 20,700 Tier 2 (General) work permits per year as, in the MAC’s view, it ‘creates uncertainty among employers and it makes little sense for a migrant to be perceived as of value one day and not the next which is what inevitably happens when the cap binds’.[2] This limit was originally put in place in 2011 on the back of a MAC recommendation which was commissioned in order to help the government in honouring its commitment to reduce net migration to the ‘tens of thousands’. Indeed, as the MAC noted, ‘the Government’s wish to limit net migration is wholly understandable’.[3]

4. For the majority of its lifetime the annual Tier 2 cap has been sufficient to meet the needs of business. Indeed, it was not met on an annual basis during six of the seven years of its operation. However, the Tier 2 (General) monthly allocations have been reached during the period from December 2017 to July 2018. There is a clear case for the level of the cap to be raised after the UK’s departure from the EU but the recommendation for its abolition is disproportionate, inconsistent with previous MAC advice, and in contradiction with the government’s still undelivered promise to the public to reduce net migration to the tens of thousands (from the current average of a quarter of a million each year).

5. Since the EU referendum, some business and employer lobby groups have raised concerns that the current level of the cap was not allowing them to fill vacancies from abroad. The MAC has recommended in the past that the Tier 2 cap should be raised to a higher level.[4] We strongly recommend that, following Brexit, an annual limit on overseas workers remains in place, although if free movement from the EU is ended, naturally the Tier 2 cap will need to be adjusted to a new level.

6. It would be a serious mistake to do away with the cap completely. This would undo the progress that has been made in refining the route since 2010. It would mean that this significant element of work migration would be entirely employer-driven. Especially since the route provides a direct means to settle in the UK after five years (provided the applicant is earning £35,000 per year), the short-term needs of an employer would effectively dictate a major strand of immigration policy largely outside political control and wholly indifferent to the many issues and consequences that result from a rapidly growing population.

7. Any adjusted cap would need to take account of EU and non-EU arrivals. The number of EU arrivals who are now in jobs that would qualify for a Tier 2 visa has averaged 25,000 per year since 2006. [5] In the year to June 2018, there were 20,100 Tier 2 General work permit grants to main applicants from outside the EU, as well as 15,900 for their dependants.

8. Separately there were 59,600 Intra-Company Transfers (ICTs) granted to non-EU migrants in the year to June 2018, of which 32,400 were for main applicants and 27,200 were for dependants. Intra-company transfers do not currently fall under the cap and we have outlined the problematic aspects of this uncapped route in recent research.[6]

b) Proposed lowering of the Tier 2 (General) skills threshold

9. The UK immigration system currently allows only those with graduate-level qualifications or above (National Qualifications Framework – or NQF - Level 6+) to take up a Tier 2 (General) work permit. Applicants must also earn £30,000 per year (if they are experienced workers) and £20,800 if they are new entrants to the labour market. Exceptions are made for jobs at the level of NQF Level 4 that are included on the Shortage Occupation List.

10. However, the MAC has recommended that, if free movement were to end, and the current non-EEA system were to be extended to EEA migrants, the Tier 2 qualification requirement should be lowered from the current NQF level 6 or above to RQF/NQF Level 3 (SCQF6 in Scotland) or above. Thus, instead of only graduate-level jobs or above being eligible, the wider range would encompass any A-level or BTEC (Business and Technology Education Council) qualification job, regardless of whether there was any evidence of shortage in the existing workforce.

c) Proposed abolition of the Resident Labour Market Test

11. The MAC also proposes the scrapping of the Resident Labour Market Test (RLMT). This currently requires employers who are seeking to fill a vacancy to prove that no settled worker could fill it. Employers are required to advertise the relevant vacancy through Universal Jobmatch and at least one other medium for 28 calendar days. In the MAC’s words: “We are sceptical about how effective the RLMT is in doing this though evaluation is hard because the criterion is subjective. We think it likely that the bureaucratic costs of the RLMT outweigh any economic benefit, but offer no opinion on its political benefit.”

12. Far from recommending its abolition, the MAC has previously said this provision should be extended to cover nurses at the same time as these roles were added to the Shortage Occupation List.[7] It is a mystery as to why the MAC would have said they were ‘supportive’ of the RLMT in 2015, and also recommended extending it in March 2016 if it has been as ineffective as they suggest in their most recent report. Similarly, businesses have accepted the need for the RLMT. As the Confederation of British Industry wrote in 2015: “Businesses accept that the RLMT alongside minimum salary thresholds, set at the right level, ensure that migrants cannot be hired to undercut the pay of other workers.”[8]

13. That does not mean that there are no weaknesses in the current operation of the RLMT. For instance, the employer is not required to help overcome barriers that UK-resident candidates might face in terms of labour mobility. Nor is there anything to encourage the employer either to incentivise workers to move to where the work is or to locate the work where the workers are. It is also difficult to enforce and job descriptions can be purposefully distorted when positions are advertised. However, these are not arguments for scrapping the RLMT but for improving and strengthening it so that it serves as a robust safeguard for UK jobseekers. As the MAC itself notes, many other countries have such provisions in place.

d) Registration of employers

14. Under the current Tier 2 system, employers must be licenced by the Home Office in order to sponsor migrant workers. It has been suggested that the government may wish to consider abolishing the requirement for employers to act as sponsors, ‘replacing them with sector bodies more as “umbrella” sponsors for their members as is done to a small extent in the Tech Nation Visa and the Tier 1 (Graduate Entrepreneur) schemes’ (although in their report the MAC have only said that the sponsor licencing system should ‘be reviewed’). They also add the sensible point that ‘an important feature of the sponsorship system is that responsibility for the migrant rests with someone who sees them on a day-to-day basis and the use of umbrella organisations would weaken this’. There is no evidence of any need to significantly loosen or alter the current Tier 2 (General) sponsor system.

Number and share of people currently in the UK at these skill levels

15. The MAC proposal to lower the skills threshold would expose a very large number of jobs to competition from a huge pool of overseas labour by loosening the criteria for entry via the Tier 2 (General) route. As Figure 1 below indicates, the MAC estimate that 32% of full-time jobs held by UK-born workers would meet the lowered qualification level.

16. If one of these 5.2 million medium-skilled full-time jobs (that is meeting the A-level threshold but below the graduate-level threshold) becomes vacant, employers may at present seek to recruit only UK and EU workers. In future, employers could look anywhere in the world to fill the role.

17. As figure 1 below also shows, UK-born workers currently hold 4.7 million jobs that are classified as highly-skilled (skilled to National Qualifications Framework 6 or above). These jobs are already open to competition from all over the world via the Tier 2 route. However, the ability of employers to hire from around the world is limited by the current Tier 2 cap of 20,700. Removing this cap, as also proposed by the MAC, would be likely to greatly increase the non-EU influx into such roles. Thus, subject to the impact of any salary threshold (see par. 18 below), just under ten million medium and highly-skilled jobs held by UK-born workers would be open to competition from workers from all over the world, many of whom will be from much poorer countries than the UK.

Figure 1: UK-born workers in full-time roles by skill level of job, MAC call for evidence (August 2017); Labour Force Survey, 2016.[9]

18. However, this does not take account of the effect of the salary threshold. The current salary threshold for experienced workers under the Tier 2 (General) route is £30,000 per annum. The MAC has recommended that this salary threshold be retained at the current level. In the MAC’s words: “This would allow employers to hire migrants into medium-skills jobs but would also require employers to pay salaries that place greater upward pressure on earnings in the sector.” The MAC has noted that only two-fifths (40%) of five million medium-skilled jobs held by UK-born workers in 2016 would meet the current salary threshold.[10]

19. In summary, combining a salary threshold of £30,000 together with the change to the skills threshold would increase the number of full-time employee jobs held by UK-born workers that employers could freely seek to fill from outside the EU via Tier 2 from 4.7 million to 6.7 million.

Potential abuse of salary level – The undercutting of UK workers as has occurred via the intra-company transfer route

20. However, there are reasons to question the effectiveness of salary thresholds as a means of immigration control. With respect to ICTs, they have said that salary thresholds can be manipulated through the use of allowances and that the minimum salary thresholds already fail to reflect actual UK labour market rates in certain occupations, especially those in the information and communication technology sector.[11]

21. Furthermore the MAC themselves identified issues with the salary threshold in their Tier 2 report (2016), saying that it is liable to fraud, difficult to verify post-entry and has an influence on the market rate.[12]

22. If employers were to make fraudulent applications under the proposed new system, the range of jobs now held by British workers that would be exposed to overseas competition would be significantly widened.

23. There is indeed a possibility that some will argue that the level of the salary threshold should be brought even below £30,000 in the course of the Immigration Bill’s journey through Parliament. However, the MAC have previously argued for increasing the threshold on the basis that doing so should result in ‘upward pressure on wages for the UK workforce… [and] will, in the long run, help address the skill shortage that leads to the recruitment of the migrant worker. Should an employer choose not to pay the higher wages then they will have to think about whether to invest in skills and training to address the shortage that way.’[13]

Incentives for non-EU workers to come to the UK

24. The Tier 2 route offers a clear route to permanent settlement provided that the applicant is earning £35,000 per year after five years. This is a major non-financial incentive for many overseas applicants. Considering that ties of family and friendship are a key driver of migration, the current population of 5.7 million non-EU born people in the UK already would be likely to act as a significant draw for such workers to migrate and settle in the UK. The same is true for 3.7 million EU-born residents, at least following the end of the potential 21-month post-Brexit transition period when the new system would come into effect.

25. Additionally, applicants could well be attracted by their higher earning potential in the UK. According to the World Bank, GDP per capita in the UK in 2017 was $43,269. This was slightly higher than for the EU as a whole ($41,126) and about 42% higher than for the New Member States ($30,527). However, per capita GDP in South Asia in 2017 was only $6,494 (about one-seventh that in the UK) and in sub-Saharan Africa it was $3,807 (about one-eleventh that in the UK).

Incentives for UK employers to hire non-EU migrants

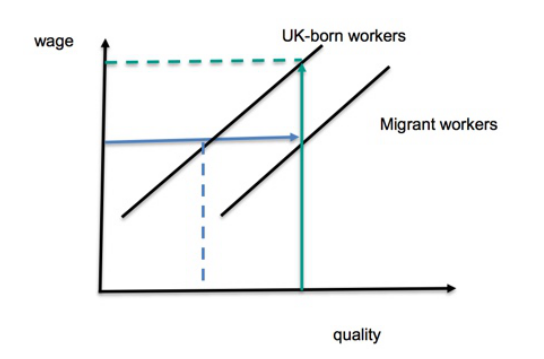

26. The MAC itself has said that EEA migrant workers are, on average, higher quality for the same wage. ‘From an economic perspective’, they note, this is equivalent to saying that ‘employers can hire the same quality workers for lower wages’. Given the much higher salary levels in the UK compared to much poorer parts of the world, the £30,000 salary threshold is likely to incentivise an employer to seek a more experienced recruit in a poorer non-EU country who is willing to work for this amount. In the MAC’s words, either ‘a lower wage can be paid for a migrant of that quality compared to a UK-born worker [the green line in figure 2 below]’ or ‘for a given wage… a higher quality migrant can be hired for that wage [the blue line in Figure 2 below]’[14].

Figure 2: Wage-Quality relationships of UK-born workers and Migrants Workers (MAC interim report, March 2018).

Potential impact on UK workers

27. Implementing the MAC’s proposals would send a clear signal that the government attaches a low priority to up-skilling our own labour force in order to fill vacancies. The MAC itself pointed in its most recent report to ‘evidence… that UK employers have been investing less in training over time and less than employers in other countries’[15]. In addition, it has previously criticised the government for seeing migrant labour as a ‘get out of jail free card’ that has allowed them to wash their hands of a past and ongoing failure to train up sufficient UK workers. As it noted in 2016: “The IT, engineering and health sectors invest insufficiently in UK residents.”[16] However, the MAC’s proposed changes to the immigration system would risk doubling-down on this hugely mistaken course of action.

28. Much commentary centres on the fact that the UK currently has a relatively low unemployment rate by historical standards. This is misleading, as eminent economists point out that wage levels can be as much if not more affected by underemployment – the underutilisation of those who wish to work more hours but cannot find suitable work.[17]

29. Oxford University’s Migration Observatory has pointed out that there are clear alternatives to reliance on immigration when a country is faced with a labour shortage. Such options include developing and adopting new technologies, mobilising the underemployed or retraining workers to meet the need for specific skills.[18] Analysis of the Labour Force Survey shows that there are around four million UK born people who are not working but are looking for work or who are working but want to work more hours, and that these levels have remained elevated while the number of foreign-born workers has increased significantly.[19] Employers often claim that they cannot find UK-born workers, but there are certainly cases where changes to working times and methods would expand the pool of local workers available to them.

30. One issue with the MAC report is that it was tasked with looking at EEA migration specifically but has made far-reaching recommendations that would have the effect of greatly increasing non-EU migration flows. Yet, the MAC’s own previous findings suggest that this could hurt UK workers in certain circumstances. The MAC reported in 2012 that an increase of 100 non-EU migrants was associated with a reduction in employment of 23 native workers over the period 1995-2010.[20] It added: “Such evidence suggests that successive governments since 2008 have been right to make non-EU migration more selective.”

31. Even the left-leaning IPPR has noted: “The inward flow of migration from other regions and abroad has resulted in a highly competitive environment at the lower end of the labour market… [in which young people in London] often struggle to get a foothold in the labour market.”[21] The MAC summarises the issue succinctly: “It is possible that the open-ended provision of migrant labour is creating an environment that means businesses and those responsible for education and training do not focus sufficient effort on increasing the skills and potential of the resident population.”[22] Post-Brexit, the immigration system should be reformed in a way which truly incentivises employers to invest in training UK young people and in improved productivity, pay and working conditions.

Potential impact on net migration levels

32. Non-EU net migration has averaged 188,000 per year over the past decade, with lower levels as the recession hit followed by higher levels recently. In 2017, non-EU net migration of 230,000 was the highest for any calendar year since 2004. The changes described above risk a substantial further rise in inflows via the work migration route, which accounts for nearly a third of current non-EU net flows according to the International Passenger Survey. Given that there would be no limit on numbers in the form of an annual cap, the only safeguard would be a salary threshold that could be manipulated so as to render an even larger number of jobs open to competition from overseas.

Public opinion

33. There is clear evidence that the public are concerned about the current level of immigration and would be particularly opposed to any changes in the immigration system that led to a rise in non-EU immigration. Research conducted by the London School of Economics in 2017 found that voters of all ages and classes wanted to see non-EU net migration cut more than EU immigration.[23]

34. Voters are also concerned about the impact of immigration on jobs. 52% of respondents told an Opinium poll last year that the current level of immigration to the UK makes it harder for people who are born here to get jobs.[24]

35. An increased level of non-EU immigration would also be likely to be harmful to social cohesion in the UK. 78% of respondents who lived in an area that had experienced large-scale immigration in recent years believe that immigration has made their community more divided.[25]

Conclusion

36. Changes to the immigration system should take account of the genuine needs of the business community but should also benefit wider society. Lowering the Tier 2 skills threshold in line with the MAC proposals would open up some seven million jobs that are currently held by UK residents or EU migrants to new or increased competition from a very large number of people from much poorer countries. Furthermore, abolishing the annual limit on the number of Tier 2 (General) work permits raises the real risk of employers piling in to take advantage of income differentials; this could result in immigration rising very rapidly indeed. If the qualifying level is to be lowered then it is essential that there should be a cap from the start before the numbers run out of control. Meanwhile, scrapping the RLMT would send entirely the wrong message to four million under-employed people in the UK. The RLMT should be strengthened, not abolished.

37. It is essential that reforms to the immigration system deliver control of our borders and a reduction in immigration levels (as was clearly promised to the electorate during the 2017 General Election[26]). However, the chief author of the proposals admits that they would not deliver full control over immigration and would likely lead to higher immigration into skilled jobs. Indeed, the effect of the measures now proposed could well be a massive rise in the level of immigration at a time when the public are very clear that they wish to see a reduction. This would be harmful to confidence in our political system, would exacerbate rapid population growth and congestion, and put added strain on public services, infrastructure and social cohesion.

Footnotes

- MAC report on EEA migration, September 2018, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… ta/file/741926/Final_EEA_report.PDF

- Ibid.

- MAC report, ‘Limits on migration’, November 2010, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… achment_data/file/257257/report.pdf

- The MAC review of Tier 2 in December 2015 recommended that the level of the Tier 2 (General) cap be raised. URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… ew_Version_for_Publishing_FINAL.pdf

- Migration Watch UK paper 391, ‘A limit on work permits for skilled EU migrants after Brexit’, September 2016, URL: https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/391

- MW451, ‘Distortion of the ICT visa route’, August 2018, URL: https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/451

- Show 20 more...

- MAC report on EEA migration, September 2018, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… ta/file/741926/Final_EEA_report.PDF

- Ibid.

- MAC report, ‘Limits on migration’, November 2010, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… achment_data/file/257257/report.pdf

- The MAC review of Tier 2 in December 2015 recommended that the level of the Tier 2 (General) cap be raised. URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… ew_Version_for_Publishing_FINAL.pdf

- Migration Watch UK paper 391, ‘A limit on work permits for skilled EU migrants after Brexit’, September 2016, URL: https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/391

- MW451, ‘Distortion of the ICT visa route’, August 2018, URL: https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/451

- MAC release, March 2016, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… _press_release_on_nurses_report.pdf

- MAC review of Tier 2, December 2015.

- Low-skilled occupations consist of National Qualifications Framework NWF2 and below; Medium-skilled occupations consist of NQF3 and 4; Highly-skilled consists of NQF6+. There are no occupations which are aligned with NQF5; as in Appendix J of the immigration rules ‘codes of practice for skilled workers’. Components do not quite add up to 16.2 million due to rounding.

- MAC report on EEA migration, September 2018.

- The MAC warned of the risk that allowances were being used to undercut, August 2009, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… _data/file/257266/mac-august-09.pdf

- MAC review of Tier 2, December 2015, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… ew_Version_for_Publishing_FINAL.pdf

- MAC review of Tier 2, December 2015, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… ew_Version_for_Publishing_FINAL.pdf

- MAC interim report on EEA migration, March 2018, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… uk-labour-market-interim-update.pdf

- MAC report on EEA migration, September 2018.

- MAC report on work migration and the labour market, July 2016, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… tion-immigrationandlabourmarket.pdf

- Blanchflower and Bell 2018 ‘Underemployment and the Lack of Wage Pressure in the UK’ http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002795011824300114

- Migration Observatory, Written evidence to House of Lords, October 2012.

- Migration Watch UK, May 2018, URL: https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/446

- MAC analysis of impacts of migration, January 2012, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… /257235/analysis-of-the-impacts.pdf

- IPPR report, ‘Learning to earning’, 2012, URL: https://www.ippr.org/files/images/media/files/publication/2012/08… earning-to-earning_Aug2012_9516.pdf

- Migration Advisory Committee, November 2010, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… achment_data/file/257257/report.pdf

- LSE blog, May 2017, URL: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/non-eu-migration-is-what-uk-voters-care-most-about/#Q

- Opinium poll, February 2017.

- Demos, May 2018.

- In the words of the 2017 Conservative Manifesto: ‘We will reduce and control immigration.’ (p. 7), URL: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/conservative-party-manifestos/… ritain+and+a+More+Prosperous....pdf