Impact of immigration in changing the UK population

27 July, 2021

Summary

1. The UK is already a crowded country yet our population is growing rapidly and is also being significantly changed by immigration at a much faster rate than has been generally understood. Indeed, 90% of growth since 2017 has been driven by immigration and subsequent children. Since 2001, the foreign-born share of the population has doubled to about nine million. Meanwhile, the number of those from an ethnic minority background, including ‘White Other’, has more than doubled to over 13 million; their share of the population rising from 10% to 21%. Just over one third of all births now involve at least one foreign born parent and one in three pupils in English state-funded schools are from an ethnic minority background. Furthermore, the share of the population of other ethnic backgrounds is already much larger amongst younger people than in the wider population. Unless firm action is taken to reduce the scale of immigration substantially, the nature of the country will be irrevocably changed.

Introduction

2. The UK is already a crowded country. Indeed England is nearly twice as crowded as Germany and three and a half times as crowded as France. Over the past 20 years unprecedented immigration by non-UK nationals (a net level of nearly 300,000 per year) has resulted in a rapid increase of the UK population as well as major changes to its composition. The number of foreign-born UK residents has nearly doubled from just over 4.5 million to more than nine million.[1] High birth rates among some immigrant communities and the younger age profile of minorities have both accelerated such changes. A return to pre-pandemic levels of immigration would add still further to these changes. There has been no serious discussion of the consequences of this outlook and certainly no general public consent for it. This paper provides background for discussion of the issues that arise. Key findings are:

- The population of rose by eight million since 2001 to just over 67 million.

- The overseas-born increase since 2001 amounted to 4.5 million, doubling the total to about 9 million; increasing their share from 8% to 14%.

- Overall, the population of Great Britain made up of other ethnicities, including ‘Other White’, has risen by seven million to just over 13 million since 2001, and now accounts for 21% of the total (up from 10%). ‘Other White’ are mainly from the EU.

- ‘White British’ as a share of the total population of Great Britain has declined by ten percentage points - from 89% in 2001 to 79%.

- Just over a third of births involve at least one foreign born parent and in some parts of London nearly 80% of births are to foreign-born mothers.

Official measurement of ethnicity and definition of terms

3. The most up-to-date formal estimates of the population by ethnic group are from the 2011 Census. The England and Wales census first asked the ethnic group question in 1991, although updated estimates are available from the Annual Population Survey (APS) and Labour Force Survey (LFS).[2] For the definitions in this paper, and other papers on this topic, we follow the 2011 definitions for both the Census[3] and the APS[4]. Where possible we use the ONS’s 2015 harmonised classification of ethnic groups.[5] The definition of terms can be found at Annex A below.

Immigration is changing the UK population

4. The UK population as a whole has increased by about eight million since 2001.[6]

Figure 1: UK population growth since 2001 (Census and ONS mid-year population estimates).

5. An average of 84% of annual population growth since 2001 has been the direct or indirect result of immigration, - that is to say immigrants themselves and the children they subsequently have in the UK (rising to about 90% or more since 2017 - see Figure 2 below).[7]

Figure 2: Population growth driven directly or indirectly by immigration, 2001-20 (our analysis of ONS statistics).

a) Changing components of UK population by country of birth

6. Since 2001 the foreign-born population of the UK has risen by 4.5 million, doubling to about nine million in by 2019/20. Figure 3 depicts time series data as it appears in the ONS’s population by country of birth tables.[8]

Figure 3: Change in size of the foreign-born population of the UK - thousands (ONS).

Questions about the true size of the EU-born population in the UK

7. It is instructive to add the two million change in the EU-born population (referred to in Table 1 above) to the 1.2 million EU-born who were already in the country in 2001 and compare the resulting 3.2 million with the new statistics published about the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS). The latter has now received just under 5 million applications by EEA nationals.[9]

8. The difference appears to be largely made up of more applications from people from Romania and Bulgaria and from southern European countries such as Spain and Portugal than the ONS originally estimated to have come to or to be living in the UK. In addition, there have been about 300,000 applications to the EUSS by non-EEA nationals who are dependants of EEA nationals.

Indirect impact of immigration - Births to the non-UK born population

9. As well as the direct impact, international migration has an indirect impact on the population as it has added considerably to the number of births but far fewer to the number of deaths. 34% of births in England and Wales in 2019 involved at least one parent who was not born here. As Figure 4 below shows, the share plateaued at around 17% between the 1970s and the late 1990s but nearly doubled following New Labour’s inauguration of unprecedented mass immigration.

Figure 4: Share of births with one or more foreign-born parent, England/Wales (ONS).

10. Since 1997, when New Labour seriously weakened a number of key immigration controls, the share of live births to non-UK born mothers has doubled from about 13% to 29%. In London, a majority of births (just under 60%) are now to non-UK born mothers, and such births now approach 80% in the London boroughs of Brent and Newham.

11. The total fertility rate (TFR) is the average number of live children that a woman would bear over her lifetime if birth rates remained constant. The graph below shows that, despite falling significantly since 2004, the non-UK born TFR remains higher than the rate for UK-born women.[10]

Figure 5: TFR by country of birth of mother, England/Wales, 2004-19 (ONS).[11]

12. Births to non-UK born mothers have run at an average of 185,000 per year in England and Wales since 2008 (averaging 26% of a total of about 700,000 per year). Figure 6 below shows that two-thirds of births to foreign-born mothers between 2008 and 2019 were to those from outside the EU (just under 1.5 million out of 2.2 million), while there were 730,000 or so births to EU-born mothers.[12]

Figure 6: Births to non-UK born mothers in England / Wales, 2008-19 (ONS).

Ethnic change in the UK since 2001

‘White British’ population

13. The ‘White British’ population of Great Britain has fluctuated between 50 and 51 million since 2001. However, the White British share of the population of Great Britain has fallen from just under 90% in 2001 to just under 80% in 2020, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Change in the ‘White British’ share of population of Great Britain, 2001 to 2019 (ONS). There are no official time series estimates of population by ethnicity for Britain. The irregularity below arises because the APS is a sample, albeit a large one.

14. Table 1 below shows that the population of Great Britain made up of ethnicities other than ‘White British’ in 2020 was just over 13 million. In the table, the 2020 population of Great Britain is broken down by ethnic group.

Table 1: Population of Great Britain by ethnic group, 2020 (ONS).

| Ethnic group | Size of population (GB) in 2020 | Share of total |

|---|---|---|

| White British | 51,065,346 | 79% |

| White Other | 4,233,279 | 6.5 |

| Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups | 1,185,188 | 1.8 |

| Indian | 1,590,427 | 2.5 |

| Pakistani | 1,282,718 | 2 |

| Bangladeshi | 624,114 | 1 |

| Chinese | 336,594 | 0.5 |

| Any other Asian background | 760,105 | 1.2 |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 2,167,738 | 3.4 |

| Other ethnic group | 1,079,391 | 1.7 |

| Total | 64,324,900 | 100% |

| Of which: Total ethnic minority population | 13,259,554 | 21% |

15. Since 2001, the population of all other ethnicities has increased by 7.4 million - more than doubling from about 6 million in 2001. As a result the ethnic minority population as a share of the total, including “White Other”, increased from about 10.3% of a total population in Great Britain of 56.5 million in 2001 to just under 21% of a total population of 64.3 million in 2020.

Figure 8: Change in total ethnic minority share of population of Great Britain, including “White Other”, since 2001 (ONS). There are no official time series estimates of population by ethnicity for Britain. The irregularity below arises because the APS is a sample, albeit a large one.

16. Recent LFS figures suggest a slight increase in the size of the ‘White British’ population. However, this has been challenged, and may be a result of weighting problems of the survey on which it is based. The ‘White British’ population declined slightly between the census of 2001 and 2011. It is hoped that the question will be clarified by the results of the 2021 census.

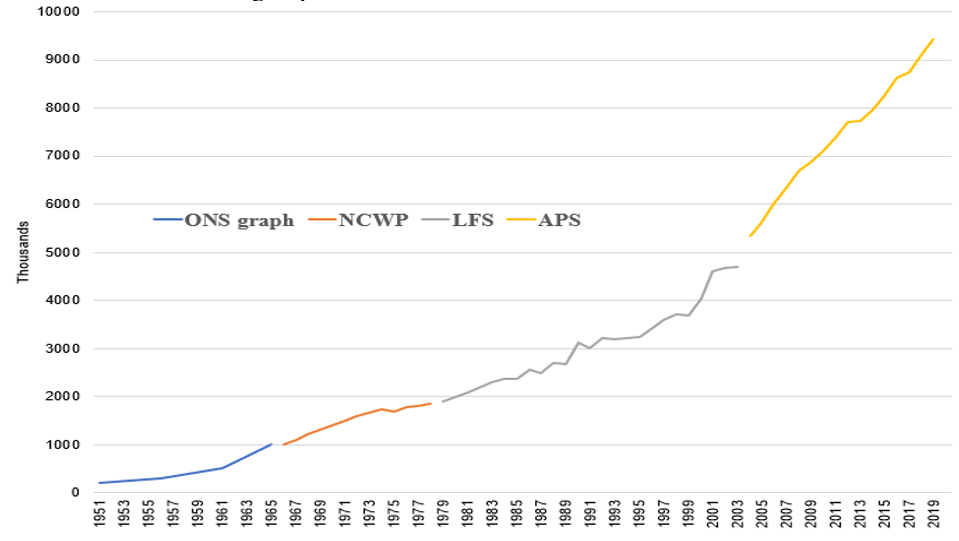

17. The ethnic minority population has, of course, been rising since the 1950s. The graph below takes a longer look at data on the size of population of other ethnicities residing in Great Britain. We have not included ‘Other Whites’ because data on groups thus described was not collected before 2001. Figure 9 shows a gradual rise since the 1950s with a significant steepening of the increase from the late 1990s.

Figure 9: Ethnic minority population not including the ‘Other White’ population, GB 1951-2020 (thousands). Office for Population, Censuses and Surveys, ONS, UK Data Service. The early part of the graph and the New Commonwealth and Pakistani (NCWP) ethnic group population estimates are from various issues of ‘Population Trends’. Information on groups termed Other White was not collected before 2001.

18. Just over half of the increase of 7.4 million in the ethnic minority population since 2001 has been linked to the arrival of those born overseas (4.4 million, or 59%). However, the charts below show a big difference between ‘Other White’ and the remaining ethnic groups.

Figures 10 and 11: Change in segments of other ethnic population, 2001-20 (ONS).

19. Between 2014 and 2019, ‘White British’ births declined from 65% of the total to 61% as a share of all live births for which ethnicity was stated in England and Wales. In numerical terms they fell by 62,000 over the same period on an annual basis (from 435,000 to just over 370,000).

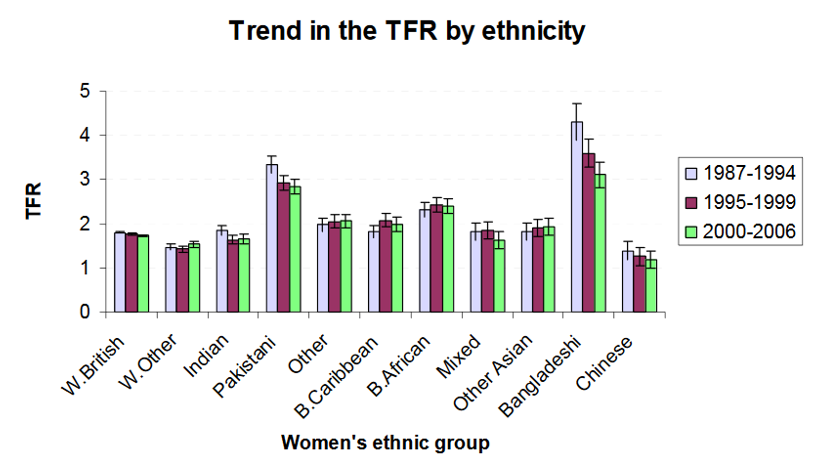

20. In contrast, while the total number of births to all other ethnicities is smaller (240,000 in 2019), the share of births to all other ethnicities increased from 34% to 39% of the total, rising slightly from 231,000 in 2014 to 240,400 in 2019 (see Figures 12 below). Figure 13 meanwhile shows that the TFR for some other ethnicities has been higher than the ‘White British’ TFR (there is limited updated data on this point available for the UK).

Figure 12: Births by ethnicity, England / Wales, 2014-19 (ONS)[13].

Figure 13: Historical trend in TFR by main ethnic group (Dubuc and Haskey, 2010).[14]

21. Younger age groups have much higher ethnic minority shares than older age groups.[15] The younger average age, higher birth rate of minority populations and a continuing relatively high level of immigration mean that the White British share of the population is likely to continue to fall.

Projections

22. There has been no recent official projection but a number of academic projections in the past decade or so suggest that, on present policies, the share of the White British in the total population will continue to decline. The results of three of the most recent projections, which all include estimates for 2061, are set out in Table 2 below:

Table 2: Academic projections of the composition of the UK population in 2061.

| Projection | Year of publication | Non-White | All other Whites | White British |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lomax et al. | 2019 | 23-30% | 10-12% | 60-65% |

| 2. Rees et al. | 2017 | 30% | - | 70 (incl. All other Whites) |

| 3. Coleman | 2010 | 36% | 10% | 54% |

23. A similar range of projections for Britain and EU countries have been made by Eurostat (Lanzieri 2011) and by some European academics. All the projections above expect the White British population to diminish in absolute and relative terms. The first two projections do not extend beyond 2061 but trends in all three point towards a situation in which the White British population would become a minority of the UK. However, all projections depend on the assumptions made and events could change them in either direction.

Make up of population in state-funded schools in England

24. The ethnic minority component of the age 5-16 maintained school population in England has increased from 16.8% in 2003 to about a third in 2020.[16] In 2020, there were 8.1 million pupils in England’s state-funded primary and secondary schools. In primary schools 33.9% of these were of an ethnic minority background (other than White British), while in secondary schools this share was 32.3%.[17]

25. The graph below shows both actual and forecast share of those who are not White British pupils in English state-funded schools. The forecast line after 2020 is based upon the average annual increase in the respective share of ethnic minority pupils from 2009-20 (0.84% for Primary Schools and just over 1% for Secondary schools).

Figure 14: Share of ethnic minority pupils in English schools (Department of Education figures on school pupils and their characteristics).[18]

26. A further potentially important factor in population growth and change is the government’s decision to offer, with effect from 31st January 2021, up to 5.4 million people in Hong Kong who are British Nationals (Overseas) the right to enter the UK and, if they wish, to become UK citizens. The government have estimated that between 123,000 and 153,700 British Nationals (Overseas) and their dependants will come in the first year and between 258,000 and 322,400 will come over five years. It is too early to judge the outcome but the numbers could be considerable.

Conclusion

27. The combination of very high levels of immigration since 2001, the generally lower age profile of the ethnic minority population and higher birth rates among some migrant groups have set in train a rapid change in the make-up of Britain’s population which raises issues that go well beyond the previous debate about net migration.

Annex A

Definition of terms:

- White British: White English/ Welsh / Scottish / Northern Irish / British.

- Any Other White background: Persons who self-identify as White but not White British, English, Scottish. This is an aggregation of the standard groups of White Other, White Irish, and Gypsy or Irish Traveller. It also includes some of other nationalities, for example Americans and Australians.

- Asian /Asian British: Asian British / Indian / Pakistani / Bangladeshi / Chinese / Other Asian.[19]

- Black / African / Caribbean / Black British: Black British / Black African / Black Caribbean / Other Black

- Mixed / multiple - Mixed / Multiple ethnic groups consists of White and Black Caribbean / White and Black African / White and Asian / Other Mixed

- Other ethnic group: Arab / Any other ethnic group

- Ethnic minority (or minority ethnic): The ONS and Cabinet Office employ the term “ethnic minorities” to describe all groups other than “White British”. On this definition, groups such as “White – Irish”, “White – Gypsy or Irish Traveller” and “White – Other” are classified as ethnic minorities. Where the White British group is not available – which is the case for most sources in this briefing – “ethnic minorities” refer to all groups other than “White”.[20]

Sources and limitations of the data used in this paper

The main sources of data for this paper are the Censuses for 2011 and 2001. There is uncertainty around the 2011 Census estimates arising from both sampling and non-sampling errors as described in the 2011 Census Quality and Methodology Information report[21]. Other data comes from the ONS’s Labour Force Survey (LFS) - a household survey whose purpose is to provide information on the UK labour market but which includes data on a variety of other variables such as ethnic group, country of birth and nationality.[22]

Another source is the ONS’s Annual Population Survey (APS) - a continuous household survey which combines results from the LFS and the English, Welsh and Scottish Labour Force Survey boosts (thus boosting the overall sample size[23]). The APS has the largest sample size of any annual UK household survey and enables the generation of statistics for small geographical areas. Sampling errors are smaller compared to those using other social survey designs because the APS has a single stage sample of addresses. As a result, it gives more robust estimates than the main LFS. APS datasets are produced quarterly with each dataset containing 12 months of data. There are approximately 300,000 persons per dataset.

The latter two ONS surveys provide estimates of population characteristics rather than exact measures and also omit many communal establishments apart from NHS housing and students in halls of residence. Members of the armed forces are only included if they live in private accommodation.[24]

Footnotes

- ONS population by country of birth figures (derived from the Annual Population Survey - APS).

- The number of tick boxes on the questionnaire grew from nine to 18 between 1991 and 2011. It is important to note that there are some people from other ethnic groups who could (or wish to) belong under any of the ‘Other’ categories.

- ONS, Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales: 2011, December 2012. URL:

- ONS, Research report on population estimates by characteristics, August 2017, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationand… opulationestimatesbycharacteristics

- ONS, Harmonised Concepts and Questions for Social Data Sources, 2015, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/harmonisation/primary-set… epts-and-questions/ethnic-group.pdf

- ONS mid-year population estimates. URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationand… ationestimates/timeseries/ukpop/pop

- Show 18 more...

- ONS population by country of birth figures (derived from the Annual Population Survey - APS).

- The number of tick boxes on the questionnaire grew from nine to 18 between 1991 and 2011. It is important to note that there are some people from other ethnic groups who could (or wish to) belong under any of the ‘Other’ categories.

- ONS, Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales: 2011, December 2012. URL:

- ONS, Research report on population estimates by characteristics, August 2017, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationand… opulationestimatesbycharacteristics

- ONS, Harmonised Concepts and Questions for Social Data Sources, 2015, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/harmonisation/primary-set… epts-and-questions/ethnic-group.pdf

- ONS mid-year population estimates. URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationand… ationestimates/timeseries/ukpop/pop

- Also see Migration Watch UK paper, ‘Impact of immigration on UK population growth’, August 2018, URL: https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/briefing-paper/452/impact-of-immigration-on-uk-population-growth The ONS also stated in 2019 that, Once the indirect effect is included, international migration (at a net level of just under 200,000 per year) accounts for 79% of the projected UK population growth over the 10 years between mid 2018 and mid 2028, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationand… onalpopulationprojections/2018based NB Net migration averaged 240,000 per year (2001-19) but net migration by non-UK citizens averaged nearly 300,000 per year. ONS, LTIM figures.

- The 2019/20 figure reflects the most recent population by country of birth statistics. However, since then the ONS have published both their RAPID-based assessments of net migration (which suggested that the International Passenger Survey had previously been underestimating immigration levels for some time) and, in July 2021, their HMRC RTI-based reweighting of the Labour Force Survey for labour market statistics which suggests that the non-UK born population has grown further and not shrunk.

- EU settlement scheme quarterly statistics up until March 2021, published June 2021, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/eu-settlement-scheme-quarterly-statistics-march-2021

- ONS, Births by parents’ country of birth, England and Wales: 2019, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsa… scountryofbirthenglandandwales/2019

- ONS, Parents’ country of birth, 2019, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsa… rths/datasets/parentscountryofbirth

- ONS, Parents’ country of birth, 2019, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsa… rths/datasets/parentscountryofbirth

- ONS birth characteristics, 2014 to 2019, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsa… rthcharacteristicsinenglandandwales

- Dubuc Sylvie and John Haskey, “Ethnicity and fertility in the UK, in Stillwell and Van Ham, Understanding Population Trends and Processes, Volume 3: Ethnicity and Integration (2010), Chapter 13, URL: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-90-481-9103-1

- Eric Kaufmann, Whiteshift, (Allen Lane, 2018).

- Department for Education, 2013, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… he_effects_of_poverty_annex.pdf.pdf

- Department of Education, ‘Schools, pupils and their characteristics’, 29 June 2017, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… ile/650547/SFR28_2017_Main_Text.pdf / January 2020, URL: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statisti… ol-pupils-and-their-characteristics

- Department of Education, ‘Schools, pupils and their characteristics’, 29 June 2017, URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/syste… ile/650547/SFR28_2017_Main_Text.pdf / January 2020, URL: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statisti… ol-pupils-and-their-characteristics

- NB The repositioning of Chinese tick box from Other category to Asian / Asian British category, and the introduction of the Arab category means there is a loss of comparability between 2001 and 2011 data for Chinese and other ethnic group.

- ONS Language and Spelling – 9. Race and ethnicity. Cabinet Office Ethnicity Facts and Figures Style Guide – Writing about ethnicity; ONS, ‘Ethnic group, national identity and religion’, https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/me… nicgroupnationalidentityandreligion; GSS, ‘Harmonised Concepts and Questions for Social Data Sources’, May 2015, URL: https://gss.civilservice.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/P3-Ethnic-Group-June-16-1.pdf

- ONS. 2011 Census Quality and Methodology Report, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/census/2011/census-data/2… y-methodology-information-paper.pdf

- The ONS states: “Each quarter’s LFS sample of 40,000 households is made up from five “waves”, each of approximately 8,000 households. Each wave is interviewed in five successive quarters, such that in any one quarter, one wave will be receiving their first interview, one wave their second and so on, with one wave receiving their fifth and final interview. Thus there is an 80 per cent overlap in the samples for each successive quarter and the sample is completely different after six quarters.”

- In some areas of the UK the boost makes up the bulk of the APS dataset, with a smaller contribution from the main LFS. The boost has a four-year wave structure instead of the five quarter wave structure in the main LFS; after the initial interview, sampled households are interviewed three more times on an annual basis. Therefore the boost for these areas may be slower to react to a change in migration patterns than the main LFS and the speed with which the APS sample responds to changes in the household population may vary across the UK.

- There are also a number of issues relating to comparability and coherence of the APS. If you wish to read more, please read this 2012 note by the ONS on the Annual Population Survey, URL: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/emp… logies/annualpopulationsurveyapsqmi