Potential impact of asylum arrangements with Rwanda

5 May, 2022

Summary

1. More than 75,600 people have reportedly arrived without prior permission by boat and lorry since 1 January 2018. Entries by boat in 2022 so far are triple the number reported by this point in 2021.[1] The UK has now agreed asylum arrangements with Rwanda which mean that those making unauthorised journeys who then try to regularise their arrival by claiming asylum can be relocated to Rwanda. That country would then take responsibility for processing applications and supporting them.[2] Australia’s experience with a similar plan suggests that, although the expense may be considerable, it should reduce attempts to come here illegally. If economic migrants and asylum shoppers (including the many asylum rejects from all over Europe and the large number who destroy identity documents) are sent abroad, the deterrent effect should be powerful. Crucially, such policies can prevent drownings and stem the evil trade of criminal traffickers. Yet the public must be given more details. The part of the agreement which commits the UK to resettling an unspecified number of 100,000 refugees currently in Rwanda has not received as much comment. The public should be informed about the numbers and the timeframe.

Introduction

2. The policy of third-country processing of asylum claimants who come to a country illegally or without prior permission has been taken up by a number of countries in the past. Now the UK has agreed a deal with the Rwandan government which bears similarities with such policies.

3. On 14 April 2022, both the UK and Rwandan governments published a five-year memorandum of understanding[3] outlining new asylum partnership arrangements.

4. According to the UK government, ‘this will see migrants who make dangerous or illegal journeys, such as by small boat or hidden in lorries, have their asylum claim processed in Rwanda. Those whose claims are accepted will then be supported to build a new life in a fast-growing economy, recognised for its record on welcoming and integrating migrants.’ Rwandan Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Co-operation, Vincent Biruta said: “Rwanda welcomes this Partnership with the United Kingdom to host asylum seekers and migrants, and offer them legal pathways to residence.”[4]

5. The exploration of such policies by the UK government is not new; they were proposed by Tony Blair when he was Prime Minister in 2003. In March of that year, in a letter to the EU presidency, he sent a document outlining the UK’s proposals to process asylum seekers in ‘processing centres’ outside Europe. Denmark and the Netherlands strongly supported the proposals, to establish ‘Transit Processing Centres’. The EU rejected Mr Blair’s proposals.

6. This paper looks at the instances where third-country processing has been tried elsewhere and considers the prospects of the UK’s new policy.

a) Summary of the UK agreement with Rwanda

7. A deal was announced between the UK and Rwanda on 14 April 2022 after nine months of negotiation. The initial agreement is to cost £120 million over five years - compared to an annual £1.5 billion bill for asylum seekers in the UK. Irregular cross-channel arrivals by boat and lorry will be assessed and those deemed inadmissible (as asylum shoppers or economic migrants) will then be sent to Rwanda.

8. It appears that only those asylum seekers who are deemed to be inadmissible to the asylum system (as under current asylum rules and under provisions of the new Nationality and Borders Bill, which has now passed through Parliament) will be considered for removal to Rwanda. Only 2 % of boat arrivals considered so far under the rules have been served with inadmissibility decisions.[5]

9. The UK has committed to undertaking an “initial screening” of asylum seekers. People who cross the Channel in small boats will undergo initial checks at the Western Jet Foil facility in Dover. Further checks will be made at a processing site in Manston, Kent. Those whose claim is deemed inadmissible may be removed to a 'third safe country'.

10. It is unclear how this will compare with the current asylum screening process. Opponents of the deal might bring legal challenges if there is no automatic right to such assistance for those facing removal to Rwanda. There may also be scope for interested parties to make judicial review applications, following on from human rights claims.

11. Rwanda has to approve all transfer requests prior to relocation and they can refuse to take people with criminal records. This could lead to complications.

12. Decisions about whether someone is fit to fly will be made (and will be challengeable) in the UK. The UK will be responsible for making and funding travel arrangements.

13. Those sent to Rwanda will initially be based at hostel in Kigali. They will not be detained but will be free to come and go from accommodation Those relocated should have access to legal assistance in Rwanda throughout their asylum claim.

14. Critics of the deal have pointed to concerns regarding the human rights record of the Rwandan government. In response, the UK government has said: “Rwanda is a State Party to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and the seven core UN Human Rights Conventions… Under this agreement, they will process claims in accordance with the UN Refugee Convention, national and international human rights laws.”[6] As journalist Dominic Lawson wrote recently: “Last year, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi, praised the government of Rwanda, specifically for the way it had provided a safe haven: 'Thanks to Rwanda, we can evacuate refugees from Libya and seek solutions for them.” The UN Refugee Agency has recommended the country as ‘a safe haven for refugees fleeing conflict and persecution’.[7]

15. Critics also suggest the agreement breaches the principle of ‘non-refoulement’ which states that no migrant can be returned to a country where they would face irreparable harm. However, Australia’s senior diplomat in the UK George Brandis has said: “At no point do our arrangements, nor as I read them the UK arrangements, breach the ‘non-refoulement’ obligations in the UN Refugee Convention.”[8] government have looked very carefully at this and ensured that Britain’s announced policy is consistent with its ‘non-refoulement’ obligations under the Refugee Convention, as is Australia’s.” The Times, May 2022. URL: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/uks-rwanda-migrant-plan-does-not-break-law-australian-diplomat-says-7hl2chf2d ]

16. Those sent to Rwanda under the deal would have no ‘automatic right’ to come back to the UK but the Home Office anticipates the possibility of UK courts making ‘bring back’ orders. Rwanda can take reasonable steps to return people to the UK if it is determined that the UK authorities are obliged to do so.

17. Under paragraph 16 of the agreement, the UK has agreed to resettle a portion of Rwanda’s “most vulnerable refugees”. This raises questions as to how many people this would involve. There are presently 100,000 or so refugees in Rwanda, the majority of whom are Congolese.[9]

18. As for whether the Rwanda deal will allow the government to save money, a government minister noted that it was anticipated ‘the amount [spent] would be comparable to processing costs incurred in the UK’.[10] However, the deterrent effect on reining in rising crossings should be enough so as to greatly the huge strains on the UK’s overwhelmed and abused asylum system in the medium to long-term, as well as on housing, services, transport and communities. As the UK faces worsening housing, health and cost-of-living crises, this plan could help ease the huge backlogs and strains facing our overwhelmed and abused asylum system and NHS, while also protecting communities now faced with major change due to rocketing illegal immigration and asylum pressure.

What do the public think of the Rwanda deal?

19. The polling on this question has not been adequate since the various questions asked of respondents do not make clear the context of illegal boat crossings which provided the backdrop for formulation of the plan. Nevertheless it has been mixed. An April 2022 YouGov poll found that marginally more people opposed the deal than supported it (42% to 35%).[11] However, a Savanta poll conducted the same month found that while 47 per cent of voters said they supported the idea, just 26 % said they were against. Labour voters were more supportive than against, while Conservative voters strongly backed the idea, by 67% to 15% and those who voted Leave in 2016 agreed with the scheme (65% to 15%).[12]

b) International case studies of offshore asylum policies in action

Denmark

20. In 2021, a Danish law was passed which allowed for refugees to be sent to a third country and for their asylum applications to be processed there. The Social Democrat-led government has since held negotiations with a handful of African countries about hosting the centres in exchange for development aid, with Rwanda touted as a likely candidate after Denmark agreed to upgrade that country’s asylum system.

21. Immigration Minister Matthias Tesfaye visited Rwanda last year and a memorandum of understanding was signed, but there was nothing firm about a refugee-processing centre. However, in April 2022, Mr Tesfaye said: "We are in dialogue with Rwanda, and we have a good cooperation based on a broad partnership, but we do not have an agreement on transfer of asylum seekers. I share the view of the Rwandan and British governments that the current asylum system is unsustainable."[13] Denmark has not yet begun deporting the estimated 400 people in its return centres, but those who are housed there cannot work, study, or cook their own meals. While they can leave the centres, they are not allowed to remain in Denmark if they do so. It is estimated that hundreds have left the country to seek refuge elsewhere in Europe.

Israel

22. Faced with a major problem of illegal immigration, Israel reached deals with third countries to take an undisclosed number of people. These countries were reportedly Uganda and Rwanda. The scheme began in 2015. Those rejected for asylum were given the choice of returning to their country of origin, or accepting a payment of $3,500 and a plane ticket to one of other countries, or being put in jail if they stayed in Israel. By 2018, Israel said some 20,000 of about 65,000 who had arrived in the country illegally had departed.

Australia

25. Our study of the way in which Australia used offshore asylum arrangements to help tackle the sharp rise in illegal boat arrivals suggests that, although the policy may be initially expensive and controversial, it can have a powerful effect in stopping the boats, tackling the criminal people smugglers and preventing needless deaths. As the Refugee Studies Centre at the University of Oxford stated: “The harsh deterrence measures served to significantly reduce the number of people smuggled to the Australian continent”.[14] For more detail on the Australian policy, please read Annex A below.

Conclusions

26. By stopping the boats, the Australians reduced the numbers going into the asylum system and prevented deaths. If (admittedly, a big if) we achieve a similar result, it will not only mean fewer people tragically dying but also stem asylum abuse, protect the UK public and save money. In the event that those coming via boat and lorry are swiftly and routinely sent to Rwanda, it could act as a powerful deterrent to those who are considering making the trip, while denying the criminal smugglers their huge profits. The most effective way of crippling the business model of the traffickers is to deny them their clients.

Annex A – A case study of Australia’s offshore processing policy

The main example of where such a policy has been tried relatively successfully is Australia. Boat people had been arriving in Australia since the 1980s when several thousand Indochinese arrived from Vietnam. In the 1990s, the origin of the flow switched to Central Asia and the Middle East. Between 1989 and 2001, a total of 259 boats arrived carrying 13,500 people.

It is also important to note that, in recent decades, there have been a number of deaths resulting from such crossings in the midst of several high-profile tragedies, including an explosion on a boat near Ashmore Reef in 2009.

From 2001, after the arrival of 433 boat people (who were rescued by the MS Tampa in August of that year) Australia implemented what was then known as its ‘Pacific Solution’ which involved offshore processing of several hundred asylum seekers in neighbouring Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Laws were passed to provide a new framework for these offshore policies. In 2001, agreements were reached with Nauru and PNG whereby those countries received multi-million dollar aid packages and coverage of the cost of processing asylum seekers. Only two boats reached Australia between September 2001 and 2006.

Australia’s former foreign minister, Alexander Downer, explained what happened when he implemented the policy of offshore processing:

”In 2001, more than 5,500 illegal migrants came to Australia by this perilous route. I realised the best way to stop it was to destroy the business model of this cruel and highly lucrative illicit trade. I established migrant centres in Manus Island in Papua New Guinea and Nauru, an island in the South Pacific, as part of a Pacific Solution initiative. Any illegal immigrant who arrived on an Australian beach was sent to one of these centres. Once word got out it worked brilliantly and by the following year, the number of illegal migrants arriving on boats had dropped to a solitary one individual.”[15]

In another article he noted:

“The way we stopped them was targeting the people smugglers’ business model. You make sure they are not able to fulfil the contract they make with the people who are paying them. If they can’t get them to their destination, migrants will stop using the route.”[16]

However, when the Labor government took power in 2008 it ended the offshore processing policy. This seemed to lead to the illegal boat crossings beginning again, and, with them, the deaths. Boat arrivals rose from 161 in 2008 to 20,587 in 2013. At the same time a large number of people died attempting to reach Australia in unseaworthy vessels. While between 2002 and 2008 there had been no deaths, between 2009 and 2013 there were 1,158 deaths of people trying to reach Australia.

In 2012, faced with an outcry over the deaths and illegal arrivals, Labor re-opened Manus and Nauru. Despite this, only a minority of boat people were transferred to the centres under the Labor government. However, following the election of a Liberal Government in 2013, the offshore processing policy resumed in earnest (as part of Operation Sovereign Borders), in tandem with an even more successful policy of boat pushbacks. This saw deaths plummet from 221 in 2013 to zero in the period 2014 to 2017.

Decline in boat crossings following introduction of policy

It is clear from the patterns of boat arrivals that the periods between 2001 and 2008 and from 2012 onwards, when offshore processing policies were implemented fully, there was a clear drop in the number of boats, with many years experiencing no boat arrivals. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Boat arrivals to Australia, 1998 to 2020. Source: Migration Watch UK graph of data from European Stability Initiative.[17]

How many people were processed overseas?

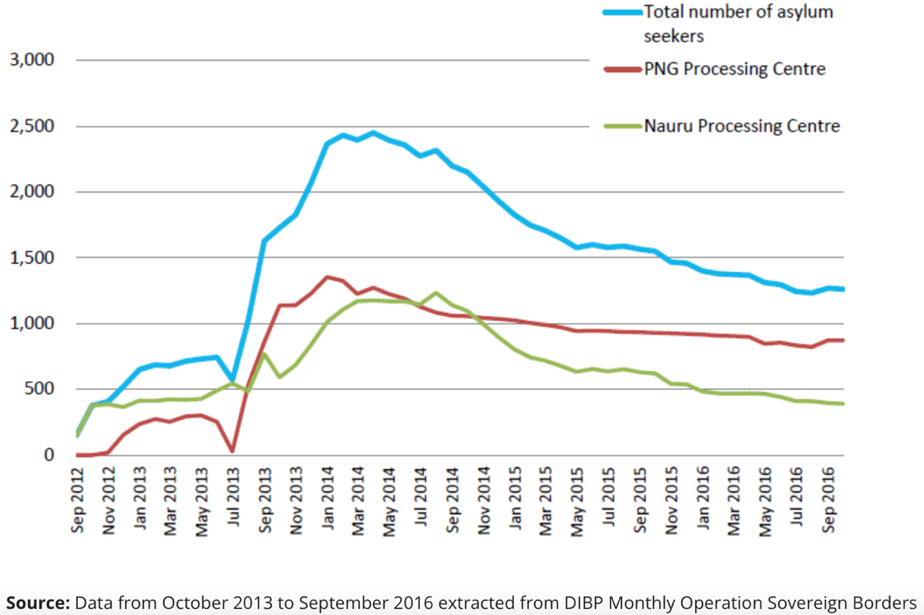

Australia’s Border Force has said more than 4,000 people were relocated between 2012 and 2019. At the peak (2014), about 2,500 people were being processed in the centres in PNG and Nauru:

- 1,544 were accommodated at offshore units between September 2001 and 2003

- The Nauru and PNG centres were closed by the Labor government between 2008 and 2012.

- From 2012, the numbers housed at both centres rose from just under 500 at the end of 2012 to 2,500 in 2014, and then dropped to about 1,300 in 2016 (See Figure 1 below).[18]

- No refugees and asylum seekers have been sent to Nauru since 2014.

- In May 2016, Australia held 1,193 people in Nauru, but by 2021 this had fallen to 107.

- Australia closed its Manus Island detention centre, after PNG's Supreme Court decision ruled it was illegal. Regional processing arrangements there ended on 31 December 2021, with the PNG Government assuming full and independent management of the residual caseload from 1 January 2022.[19] By the time of the arrangement ending, there were 120 asylum seekers and refugees remaining in PNG. They were given the option of resettling there or moving to Nauru.

- By 2022, the number of what the Australian government called ‘transitory persons’ in Nauru was 112 (83 of whom were recognised to be refugees).[20]

Figure 2: Asylum seekers processed in Nauru / PNG. Australian Government.

What happened to those who went to these centres?

Policies such as these can offer those being processed the choice of a safe alternative destination to the one for which asylum seekers set out. Over the years, those who ended up in PNG and Nauru had the option of departing for another safe country. For example, in 2014, 210 people left the centres for Iran, 38 for Iraq, 22 for Lebanon, 9 for India, 4 for Bangladesh, 4 for Pakistan and 4 for Sri Lanka. There is no record of whether any of these countries were ones from which those who had claimed asylum had fled.

In addition, in 2016, Australia and the United States agreed a resettlement arrangement. It provided resettlement opportunities in the United States for up to 1250 refugees under regional processing arrangements. As of 28 February 2022, the United States resettlement arrangement has enabled 998 individuals (401 from Nauru, 426 from PNG and 171 from Australia) to resettle in the United States. Many refugees have had their resettlement applications approved and are at various stages of pre-departure activity, while many others have applications in train. Meanwhile, four refugees agreed to depart Nauru in June 2015 to be settled in Cambodia.

In March 2022, a three-year deal was announced for up to 450 refugees from Australia's regional processing centres to be resettled in New Zealand.

Controversy

To be sure, Australia’s offshore processing policy has been controversial. During Australia's eight-year presence in Papua New Guinea there have been major incidents of violence, including hunger strikes, riots and the murder of an Iranian asylum seeker by guards.

Meanwhile, a number of non-governmental organisations and the UN have criticised Australia's centres in PNG and Nauru for substandard conditions. However, despite some suggesting that the policy is inhumane, it cannot be denied that Nauru and PNG are safe countries and that Australia and those nations were within their rights to agree bilateral arrangements to deal with an illegal immigration scourge that was leading to scores of deaths and profiting criminal people traffickers.

Cost

The government has said that the UK’s agreement with Rwanda will cost £120 million over five years. This in contrast with the current cost of the asylum system which is £1.5 billion per year. £1.2 billion per year is also currently being spent on hotel accommodation for 25,000 asylum claimants, including in four-star establishments.

By contrast, the arrangements in Nauru appeared to have cost just over half a billion dollars per year between 2017 and 2021 (£283 million). Responses to Senate questions show that from November 2017 to January 2021, the Australian government spent more than $1.67bn on “garrison and welfare” for those held on the island – averaging out at about $481 million per year, or £272 million)

The cost of running the Nauru arrangements in 2016 were reported to be about $534 million per year. By 2021, estimates for the cost to accommodate a far smaller number of people (107 compared with 1,193 in 2016) were just under $600 million per year.

By the Australian government’s own projections it will spend $811.8m (£460m) on offshore processing in 2021-22.

In 2017 Australia was reported to be paying $70 million (£37 million) in settlement money to more than 1,900 people who had sued for harm.

Although the cost of the Australian scheme has been significant, this must be balanced against what the projected cost would have been were boat arrivals to continue at 20,000 per year (the number they reached in 2013). This figure has already been reached for the UK (in 2021, there were 28,500 arrivals). The deterrent effect of this policy should have the effect of reining in in the medium to longer-term, what would otherwise be steadily rising costs and knock-on impacts (unquantified negative externalities) such as housing pressure, overcrowding, traffic gridlock, loss of green space and strains on services.

Stopping deaths at sea

As government minister Tom Pursglove put it in late April 2022: “We believe this is an important policy intervention that will shift the dynamic and help to preserve lives. That is a fundamental imperative and we cannot put a cost on it.”[21] Despite both the controversy and the expense, offshore processing appears to be one of a range of sub-optimal solutions. By helping deter people from setting off on dangerous sea voyages, it can clearly prevent deaths. The graph below shows deaths at sea between 2000 and 2017. The data suggests that the number of deaths fell off when offshore processing policies (among others from 2013 onwards) were in place. From reaching a peak of 411 in 2012 after Labour closed the offshore processing centres in PNG and Nauru, the number of deaths dropped dramatically to zero from 2014 onwards. Figure 3: Deaths at sea of those attempting to reach Australia. Migration Watch UK graph of data from the European Stability Initiative. [22]Footnotes

- View our very popular and regularly updated Boat Tracking Station, URL: https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/news/2020/05/11/arrivals-via-dea… hannel-crossing-from-safe-countries

- See Home Office press release, 14 April 2022, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/world-first-partnership-to-tackle-global-migration-crisis

- Memorandum of Understanding, 14 April 2022, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/memorandum-of-understa… the-government-of-the-republic-of-r

- Home Office press statement, 14 April 2022.

- The Times, April 2022, URL: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/just-2-of-migrants-will-be-sen… anda-under-existing-rules-g9q707f5p

- Hansard, 14 April 2022, URL: https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2022-04-14/%31%35%34%34%38%31

- Show 16 more...

- View our very popular and regularly updated Boat Tracking Station, URL: https://www.migrationwatchuk.org/news/2020/05/11/arrivals-via-dea… hannel-crossing-from-safe-countries

- See Home Office press release, 14 April 2022, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/world-first-partnership-to-tackle-global-migration-crisis

- Memorandum of Understanding, 14 April 2022, URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/memorandum-of-understa… the-government-of-the-republic-of-r

- Home Office press statement, 14 April 2022.

- The Times, April 2022, URL: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/just-2-of-migrants-will-be-sen… anda-under-existing-rules-g9q707f5p

- Hansard, 14 April 2022, URL: https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2022-04-14/%31%35%34%34%38%31

- Mail Online, April 2022, URL: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-10749621/DOMINIC-LAWSO… callous-scheme-Libyan-migrants.html

- Mr Brandis added: “It is not the obligation of a state, to which an application for asylum is made, to settle in that state those applicants if they are successful. It is the obligation of the state not to refer them to a nation from which they have a justified fear of persecution — under the formula of the Refugee Convention — and to facilitate their settlement in a nation in which they will not face those threats, either onshore or offshore... I will be absolutely confident that the lawyers who advise the [UK

- UNHCR, early 2022, URL: https://reporting.unhcr.org/rwanda

- Hansard, 19 April 2022, URL: https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2022-04-19/%31%35%35%36%30%30

- YouGov poll, April 2022, URL: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/travel/survey-results/daily/2022/04/14/8bb29/1

- MailPlus, April 2022, URL: https://www.mailplus.co.uk/edition/news/172099/exclusive-voters-huge-backing-for-rwanda-plan

- BBC News, April 2022, URL: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-61106231

- Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford, October 2006, URL: https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/files-1/wp36-politics-extraterritorial-processing-2006.pdf

- Daily Mail, URL: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-8796535/Former-Austral… rew-Downer-advises-UK-migrants.html

- The Times, URL: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/albanian-airlift-for-illegal-migrants-p0mmkfz6f

- European Stability Initiative, June 2021, URL: https://esiweb.org/sites/default/files/newsletter/pdf/ESI%20-%20T… Australia%20-%207%20June%202021.pdf

- Australian government, ‘Australia’s offshore processing of asylum seekers in Nauru and PNG: a quick guide to statistics and resources’, URL: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments… ck_Guides/Offshore#_Total_number_of

- Australian Ministry of Home Affairs, URL: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about-us/what-we-do/border-protect… egional-processing-and-resettlement

- Australian Ministry of Home Affairs, URL: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about-us-subsite/files/population_… esettled_as_at_28_february_2022.pdf

- Hansard, 25 April 2022, URL: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2022-04-25/debates/C707BE6C-A96A-40E5-AF8A-D04B7CA010A0/web

- European Stability Initiative, June 2021, URL: https://esiweb.org/sites/default/files/newsletter/pdf/ESI%20-%20T… Australia%20-%207%20June%202021.pdf